Australia’s first confirmed ancient underwater archaeological sites have been discovered in the Pilbara.

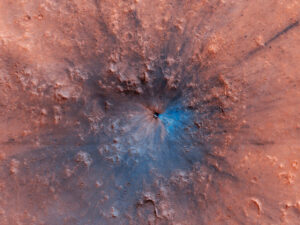

A team of researchers located the two sites in the Dampier Archipelago, off the coast of Karratha.

At the first site – Cape Bruguieres – researchers found more than 260 artefacts in 2.4 metres of water.

The area has been underwater for more than 7,000 years.

Ancient furniture

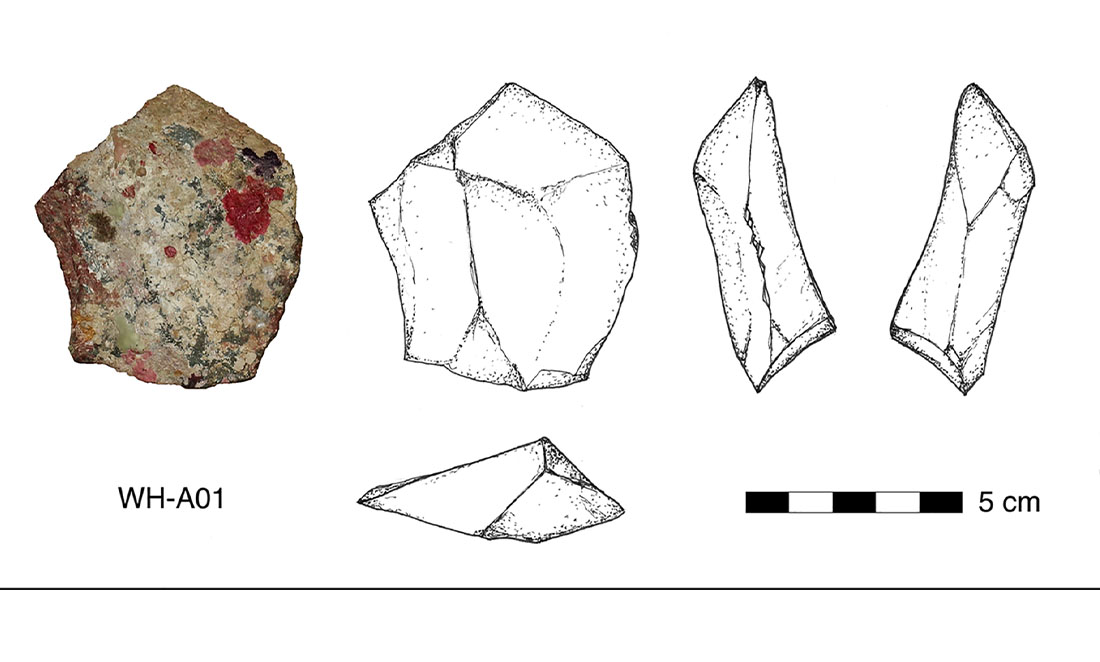

According to Professor Jo McDonald from UWA’s Centre for Rock Art Research + Management, the site contains artefacts ranging from small hand tools to large “furniture”.

“[It’s] the sort of stuff that people leave in places because it’s too heavy to carry around,” she says.

“Things like grinding stones that people came back [to] time and time again.”

Jo says it appears as if people made stone tools at the site, and then used them for things like woodworking and processing animal flesh.

The team also recovered a single artefact, at a freshwater spring called Flying Foam Passage, 14 metres below the surface.

The site has been covered by water for more than 8,500 years.

Underwater search party

Finding archaeological sites in the ocean is tough.

The researchers scoured the archipelago over six field trips, using aerial surveys, sonar and dive teams in a targeted campaign.

“People have been looking for underwater Aboriginal archaeology in Australia for decades,” Jo says.

“The real challenge is to find a landscape where the probability of there being sites is high.”

“But you also have to look for an area where you have the conditions to actually retain that information.”

Perth for instance – with its sandy beaches battered by storms every winter – is unlikely to contain a lot of well-preserved archaeological sites in shallow waters.

In contrast, the archaeological sites on the Dampier Archipelago were protected from harsh weather by bays and hard rocks.

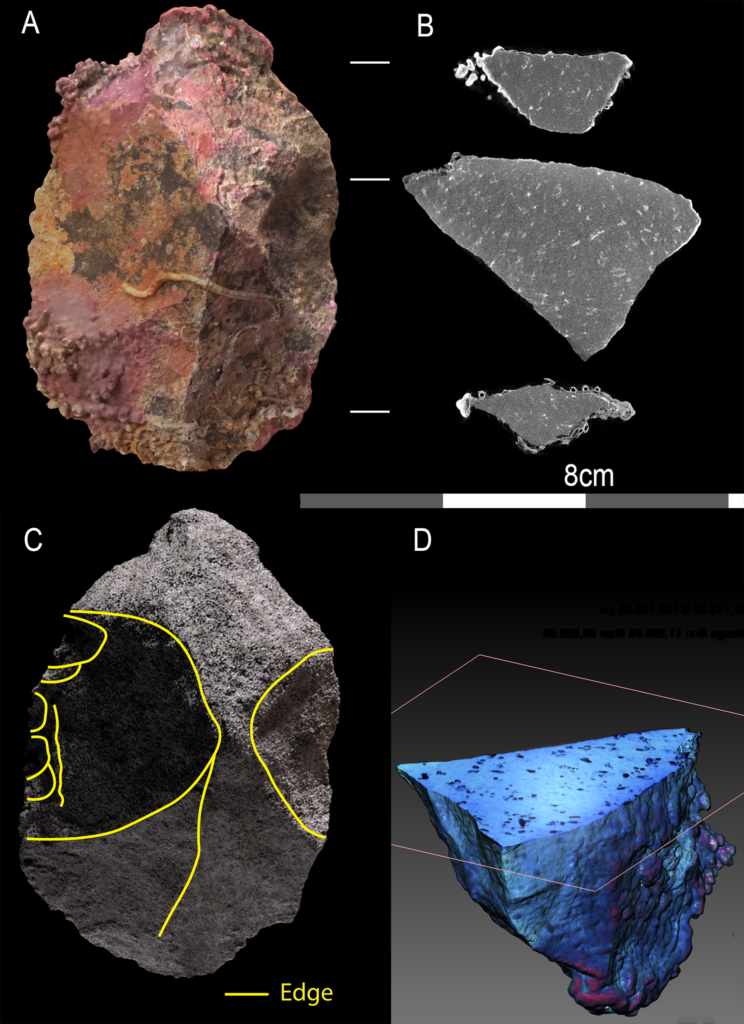

When the research team did strike archaeological gold, it still wasn’t easy for the divers to initially tell the difference between an ancient stone tool and an underwater rock.

“We couldn’t be sure, when we started bringing up these barnacle-covered objects, whether they were artefacts,” Jo says.

“They actually had to be brought to the surface and then looked at with a microscope.”

According to Jo, the team used high-tech laser machines that imaged the surfaces through the marine growth to show the sharp edges of the artefacts.

According to Jo, the team used high-tech laser machines that imaged the surfaces through the marine growth to show the sharp edges of the artefacts.

“That was when we really could demonstrate that we actually had the characteristics on those rocks to show that they had been modified by humans, and not moved by water into their current locations under the sea,” she says.

First of many

Maritime archaeology is common in Europe.

On the Mediterranean and Aegean coastlines alone, scientists have uncovered human settlements from the Neanderthal, Palaeolithic, Iron Age, Classical and Ottoman periods.

Jo and the research team believe the recently-discovered Indigenous sites will be the first of many in Australia.

“We have thousands of sites across the Dampier Archipelago above the water,” she says.

“And the sea level has only been in its current location for the last 7,000 years – a fraction of the time that Aboriginal people have been living on the Pilbara coast.”

“This really is just the beginning.”