In its most basic form, science involves making an assumption and trying to prove or disprove it by collecting data through experimentation or observation.

Sometimes our curiosity and pursuit of knowledge can lead us down some concerning pathways. This is where ethics and peer review come in.

“Research ethics is a very specific area where there are certain checks and balances in place to make sure that any research that impacts living beings meets certain basic standards,” says Anne Schwenkenbecher, Associate Professor of Philosophy at Murdoch University.

According to Anne, humans are social beings that abide by a set of social rules. Some of these rules, like not randomly killing each other, are clear cut and agreed upon by the majority.

Other rules require more nuance and discussion – enter ethics.

“Ethics is a social practice,” says Anne.

“An ongoing activity where we work out what is OK and not OK. It’s a collective argument and decision making that is always slowly evolving.”

Credit: National Cancer Institute/Unsplash

DRAWING THE LINE

Scientists must get approval from a relevant ethics board before beginning their research.

In Australia, there is no single governing body that overlooks the ethics of all research.

Instead, the Australian Research Council states that “responsibility for the various aspects of research integrity is shared among institutions that conduct research, funding agencies, agencies such as Ombudsman Offices in the jurisdictions, Crime and Corruption Commissions in jurisdictions and the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA)”.

While this may sound flawed and messy, many of these institutions and their ethical principles are based on internationally accepted codes of conduct such as the Nuremberg Code or the Declaration of Helsinki – two significant sets of guidelines for ethical research involving humans.

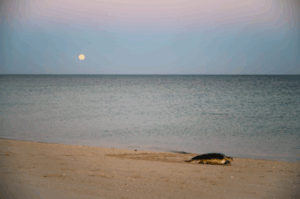

But it’s not all about humans.

“Ethical principles extend to anything that could be harmed, including the environment,” says Anne.

For example, some of the controversy around Colossal Biosciences, which aims to resurrect extinct species, is the ethical questions around resource management.

“Given limited resources, is this what we should be spending time and money on or are there more urgent things?” says Anne.

“It’s a tricky question because we can probably ask this about many things. But most ethical questions are tricky questions.

“That’s why we have these ethics boards … they’re all part of a collective endeavour to work out what is the right thing to do.”

Credit: Colossal Biosciences

Ensuring best practice

If the relevant ethics board has given the tick of approval, the research has been conducted and conclusions drawn, the next step is publication – preferably in an academic journal.

For that to happen, the research must be submitted for peer review.

“Peer review is meant to ensure that we produce the best information that we can, with the means that we have,” says Anne.

Peer reviewers are a team of anonymous and independent experts within the relevant field of science.

When they receive a submission, they check that the process that was taken and the arguments that were made are original and valid.

If something looks off, they will provide feedback and delay publication. If all looks good, the research will be formally published in the journal.

Credit: Andre William/Unsplash

You may assume that the research – and its findings – come to a clear conclusion once published in a journal, but publication is just the beginning.

Much like ethics, science is cumulative and always open to further developments. Once you share your findings with the world, it is incorporated into an existing body of knowledge.

It may spark inspiration in other scientists to conduct their own research and completely disprove or further expand on your findings.

Science is an infinite cycle of questions and answers. And depending on your outlook, that’s both scary and beautiful.