Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic disease of the central nervous system. The body attacks a nerve coating called myelin that protects the nervous system.

Symptoms include vision impairment, sensory symptoms, dizziness, memory and psychological problems, pain, tingling and tremors, among others.

In 2021, there were over 33,335 Australians living with MS – a 30% increase since 2017.

There is no single known cause for MS or a cure.

However, WA scientists have helped reveal a piece of the puzzle that brings hope to those with the debilitating degenerative disease.

GENE SLEUTHS

WA researchers were part of a global collaboration that statistically linked a gene to MS.

The International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium (IMSGC) consists of scientists from around the world.

Here in WA, Dr Marzena Fabis-Pedrini and Professor Allan Kermode from the Perron Institute led the WA component of the study.

They collected and processed DNA samples and curated extensive clinical data from 327 WA patients.

Marzena and Allan are co-located at the Centre for Molecular Medicine and Innovative Therapeutics, Murdoch University.

CRACKING THE CODE

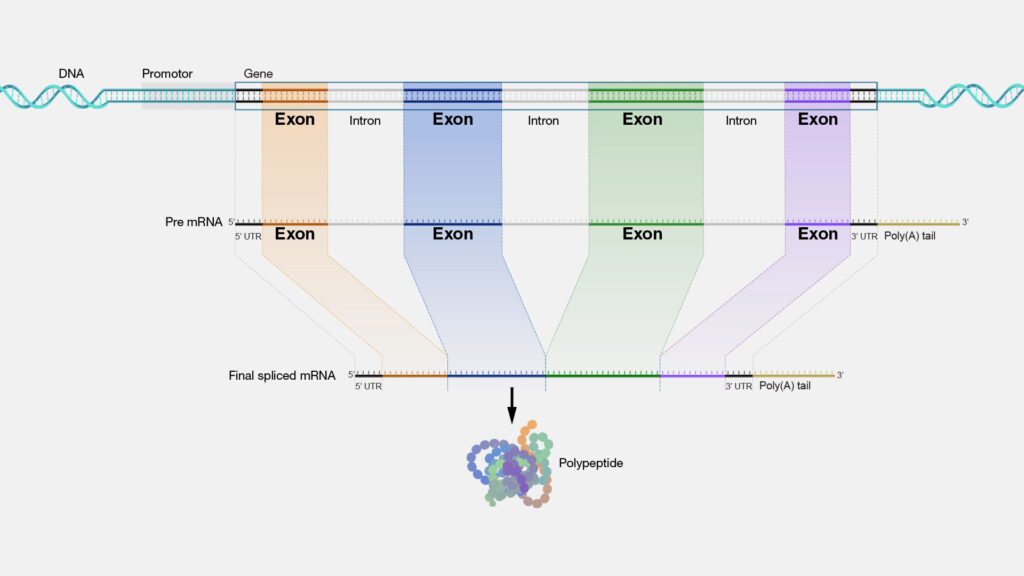

DNA is the biological code that stores plans for how our body grows and operates.

Genes are the segments of this code that our bodies read for direction. It’s passed from one generation to the next alongside DNA.

Gene variants are part of what makes you unique. Variants come from differences in your DNA. These differences may change a gene’s function.

Variants are important for evolution and individuality, but they can also contribute to diseases.

PICTURE HERE

The WA patient data was added to a collection of 22,000 patient samples collected around the world to build a genome-wide association study.

This type of study is a way to learn about genes without testing them – since we don’t want to experiment on people!

The study linked the likelihood of having a genetic variant called rs10191329 with the likelihood of having MS. The variant gene was also associated with faster progression of the disease.

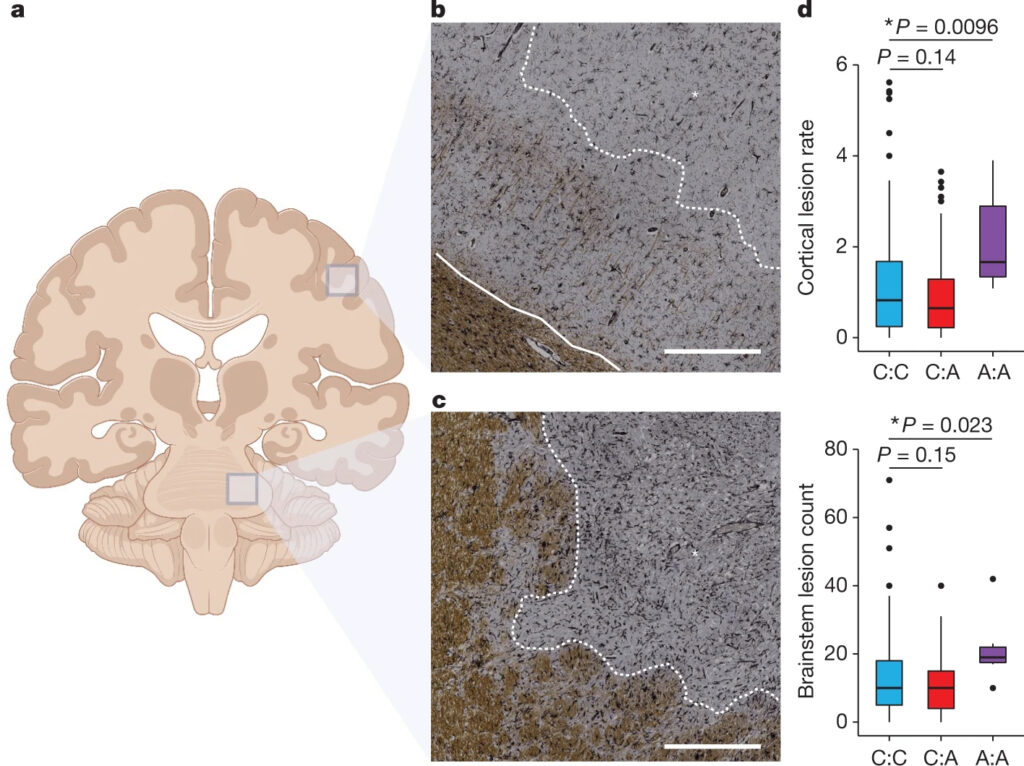

It was found that patients born with two copies of the gene variant used a walking aid 3.7 years earlier than those without both copies. They also had signs of MS pathology in their brain stem and brain.

A UNITED EFFORT

The IMSGC joined forces with the MultipleMS Consortium to run the global study – led by researchers from the University of California San Francisco and the University of Cambridge.

More than 70 institutions were involved.

They looked at the genes and medical records of over 22,000 patients, then compared them to 7 million genetic variants.

Marzena says it was a long-term team effort.

“We are part of the Australian and New Zealand MS Genetics Consortium (ANZgene), and most of the members took part in this study,” she says.

“We have been working on this project for five years.

“There were many steps involved, including patient blood collection, DNA extraction and DNA analysis.”

MILESTONE MARKER

Patients with two variant copies of rs10191329 were more likely to have MS progress faster. They were also more likely to require a walking aid earlier than those without both copies.

Autopsies of deceased patients revealed they were 1.83 times more likely to have lesions in their brainstem.

The gene variant they identified is called an ‘intron’. Introns are non-coding parts of the DNA that can affect how the body reads neighbouring genes.

Its neighbours are interesting too.

THE MS GENE NEIGHBOURHOOD

The variant gene sits between two other exons (reading genes).

Called DYSF and ZNF638, they are involved in the nervous system.

“DYSF is involved in repairing damaged cells, and ZNF638 helps to control viral infections by mediating and silencing unintegrated viral DNA.”

LOOKING AHEAD

Researchers don’t know why rs10191329 may contribute to MS.

But by identifying it, they may be able to discover a mechanism and design drugs to help people with MS.

“It’s very early days … but work is already under way to develop this area,” says Marzena.

“The discovery of genetic variants can pave the foundation for a generation of new treatments.”

“We will be able to identify patients with this variant with a prognosis of faster progression and treat them accordingly once the new treatments [are] developed and accessible.”

Their discovery also has implications for other neurological conditions, such as Parkinson’s disease and motor neurone disease.