The creamy, white lotion miraculously protects our skin from the Sun’s harmful UV radiation.

Lately, sunscreen has received some controversial bad press from influencers on social media platforms like TikTok.

The claims include that it’s toxic, blocks the natural absorption of vitamin D and even accrues in the bloodstream.

So is sunscreen good or bad for us?

FROM OZONE TO NO-ZONE

It’s no secret that Australia has the highest rates of skin cancer on Earth.

As many as two out of three Australians will be diagnosed with skin cancer during their lifetime, according to the Cancer Council.

Australians often blame this high statistic on an apparent hole in our section of the ozone layer.

While it’s true there is a hole in Earth’s ozone layer, this gaseous stratospheric gap occurs only over Antarctica and only during spring.

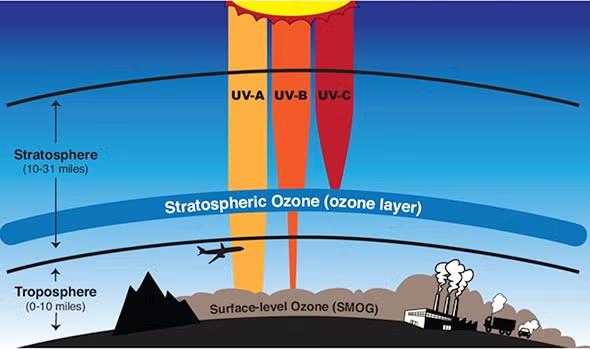

Caption: The ozone layer reduces the amount of UV light that reaches our skin, but doesn’t stop it completely.

Credit: NASA

That doesn’t mean the Sun isn’t more damaging here.

Australia’s UV levels are among the highest in the world and are usually measured as extreme throughout summer. This is a result of the elliptical orbit of the Earth around the Sun.

This, coupled with a predominantly fair-skinned Anglo-European population, is why Aussies need to prioritise sun protection.

“AND TRUST ME ON THE SUNSCREEN”

Modern sunscreens are often cited to have originated in Australia in 1938, but the historical use of sun protection dates back as far as 3000 BCE.

Ancient Egyptians used crushed lotus petals and rice bran to dissuade the North African sun.

Even the ancient Greeks smothered their chiselled chests in olive oil, which reportedly has an SPF of around 8. (Please don’t try this at home.)

Currently, there are two primary types of sunscreens, which work to resist UV radiation in different ways.

Mineral sunscreens like zinc oxide (often marketed as zinc) create a thin layer of metals that physically block some of the Sun’s UV rays.

Chemical sunscreens convert the UV rays into heat to lower the sunburn risk.

Caption: Naturally occurring zinc, applied directly to the skin in oxide form, is a useful but less-popular sunscreen

Credit: Alchemist-hp (talk) (www.pse-mendelejew.de), FAL, via Wikimedia Commons

SUN PROTECTION FACTOR

Professor Rachel Neale researches sunscreen and cancer at QIMR Berghofer.

“It’s important to be clear that sunscreens were originally designed to stop sunburns,” says Rachel.

“So all the testing of sunscreen that is done is how well it works to stop a sunburn.”

“The SPF (sun protection factor) number is about effectiveness at stopping burns, but it turns out that sunscreen can also reduce the risk of skin cancer.”

Rachel says, “Australians are advised to use it on all days when the UV index is forecast to get to 3 or greater. That’s all year for some parts of Australia and most of the year for everywhere else.”

“But that’s really the base level of protection.”

WHAT THE SPF?

Rachel says an over-reliance on sunscreen can be counterintuitive.

“People use sunscreen to avoid getting sunburnt and therefore stay outside for longer than they otherwise would,” says Rachel.

However, both types of sunscreen still let some UV through.

In fact, the SPF number is a measure of how much longer it would take you to burn than it would without wearing any sunscreen.

If you would normally get burnt in 10 minutes at the current UV rating, wearing SPF 30+ means it would take roughly 300 minutes to receive that same burn.

Caption: NASA’s high-resolution image of our Sun

Credit: NASA/SDO (AIA), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Provided, of course, you are wearing the correct amount of sunscreen. A 5ml teaspoon for each limb, face, front and/or back of your body that’s exposed to the sun. (Which nobody does.)

Exposure to UV radiation causes genetic mutations and DNA damage, which is the origin of most skin cancers.

Essentially, sunscreen is most effective when used correctly.

It’s just one of the five sun protection pillars: slip on a top, slap on a hat, seek shade, and slide on a pair of sunnies.

WHERE’S THE FIRE?

Despite all this, certain corners of social media are promoting the view that sunscreen isn’t all it’s made out to be.

In recent years, some chemicals have been banned in US states due to the damaging effect they have on beachside waters and coral reefs.

It seems concerns were raised after two recent studies noted certain materials present in chemical sunscreens appear to accumulate in the bloodstream.

There are some links to neurotoxicity and the endocrine system, but the evidence is very inconsistent and a long way from becoming solid proof.

Rachel suggests that, although these studies are important, it likely isn’t the full story.

One study analysed chemical sunscreens administered at the maximum dosage, which is far higher than experts advise.

Caption: A young kid puts sunscreen on their face.

Credit: Kindel Media via pexels

“I think it’s really important to note that that does not mean they’re harmful,” says Rachel.

“The US Food and Drug Administration, the FDA, said that we actually need to do some more research on these sunscreens to ensure that they’re safe. But they did not say they are not safe.”

More research is always a good thing when it comes to public health, but currently the science seems to imply there’s little cause for alarm.

Even if these chemicals are absorbed into the blood, concrete evidence is yet to emerge of any negative health impacts.

Since sunscreen was invented, there has been extensive research into its efficacy and potential side effects.

At this point in time, one thing is certain. “Skin cancers kill people, they disfigure people and we spend a fortune treating them,” says Rachel.

“We spend more on treating skin cancer than on any other cancer in Australia.”

The best advice is to use sunscreen as directed. In reasonable amounts, in conjunction with several other sun-protection strategies.