University of British Columbia and UWA researchers estimate nearly 10 million tonnes of fish are thrown overboard each year.

“The waste is shocking, given concerns about food security,” UWA’s Professor Jessica Meeuwig says.

“Fish discards are a massive problem.”

The study is part of the Sea Around Us project.

The project collects data from every fishery in the world and assesses their impact on marine ecosystems.

The research is the result of 15 years’ work and the first look at fish discards on a global scale, Jessica says.

SOMETHING SMELLS FISHY

Fish are tossed back when they’re damaged, undersized or bycatch.

Bycatch is unwanted fish or other marine life unintentionally caught in nets.

A commercial fishing practice called ‘high-grading’ is a problem too.

High-grading is when fish are caught and frozen but dumped overboard when a second catch is caught.

This happens because the second lot is fresher and perhaps bigger or the fish are worth more money.

Commercial fishing fleets are the biggest culprits, but recreational and illegal fishers contribute too.

Recreational fishers often reel in fish they don’t want to eat or that’s undersized, out of season or over their bag limit.

Anglers can minimise bycatch by using the right rig for the target fish species and handling unwanted fish carefully so they swim away unharmed when released.

WHAT A WASTE

WA’s fish discards are about 5% of the total yearly recorded catch, Jessica says.

She says it’s a relatively small problem in the Indian Ocean compared to other oceans, but discards have increased since 1980.

The researchers compared the amount of fish thrown away over time.

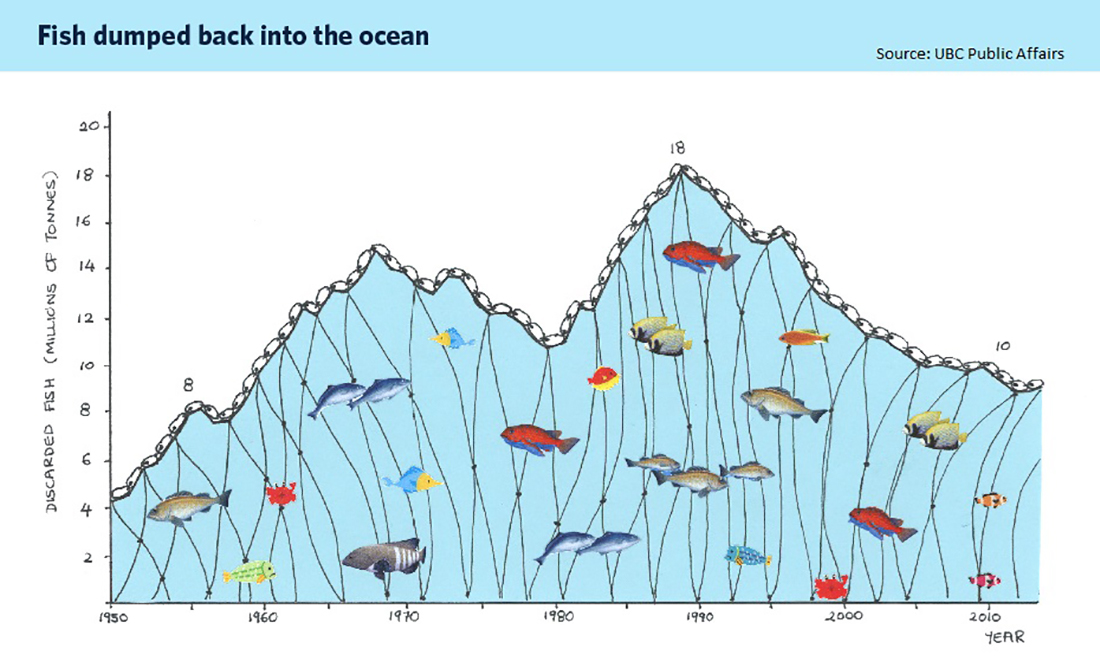

In the 1950s, about 5 million tonnes of fish were dumped each year.

By the 1980s, fish discards had more than tripled to 18 million tonnes.

Over the past decade, it has decreased to 10 million tonnes.

But before you get your hopes up, researchers believe the decline indicates depleted fish stocks, not less irresponsible fishing.

“Discards are now declining because we have already fished these species down so much that fishing operations are catching less and less each year … so there’s less to throw away,” Sea Around Us senior research partner Dr Dirk Zeller says.

FISHING FOR THE FUTURE

“Most people don’t think about where their fish comes from or how it ended up on their plate,” Jessica says.

This needs to change to address dwindling fish stocks and fisheries’ sustainability.

“We need to start thinking strategically about fisheries and have a hard discussion about what fisheries are inappropriate, like super trawlers,” Jessica says.

Large, totally protected marine reserves could help overfished species bounce back from poor fishing practices and fisheries management.

“No-catch areas are the engine rooms for resilience and recovery,” Jessica says.

She says a new attitude towards marine conservation is critical.

“We need to look at the oceans the way we look at the land,” Jessica says.

“Instead of every single hectare being wheat or sheep grazing, we have areas of natural habitat to protect biodiversity.”

“We need to start looking at our oceans the same way instead of with the view that everything is open access.”

The research was published in Fish and Fisheries.