As humans, there are a couple of trends that are obvious among our species:

- We make a lot of babies.

- We have to constantly advance farming practices to feed those babies.

Feeding a growing population has been a challenge for many generations, and advancements in agriculture have helped us fill billions of bellies.

We’re now looking down the barrel of a 9 billion strong human population by 2050, and one of the first questions on people’s minds is how are we going to feed them all?

I spoke to 2017 Premier’s Science Award Scientist of the Year, Professor Harvey Millar of Plant Energy Biology (PEB) to help answer this question.

9 billion mouths to feed

It’s a daunting number, but what does it really mean in the context of food production?

“In the next 50 years, we actually have to grow more food than we have grown since the dawn of civilisation,” Harvey tells us.

With babies being born faster than we can feed them, the future is rife with challenges. But I was surprised to learn, in terms of global food security, Australia is sitting pretty.

“Australia has a remarkable position in the world of agriculture, because we are a very agriculturally productive country and we have a small population,” Harvey says.

“We produce about four to five times more food than we need to feed our population, so Australians aren’t going to go hungry.”

While we might be flushed with food, other countries will be feeling the pinch, which means they’ll look to us to pull them through.

“There’s 100 million people being sustained on the planet at the moment because of Australia’s efforts,” Harvey says.

“We have a financial benefit of feeding those people, and maybe we have a moral responsibility. If we don’t feed them, who is going to feed them?”

But before you get too comfortable, Australia still has a few challenges of its own.

Drought, disease and salty soils

In Australia, we have a lot of room to farm, but conditions can be harsh and unforgiving.

“We produce all of the food that we do with a variety of quite harsh conditions that operate in Australia,” Harvey says.

“So things like salinity and alkalinity of our soils … and drought, flooding and frosts are the really major threats.”

“There are disease threats as well, but those climactic threats are substantive.”

So our main challenge is breeding robust plants that can withstand the dry and salty land.

The key to doing so is hidden in their DNA.

Enhancing energy efficiency

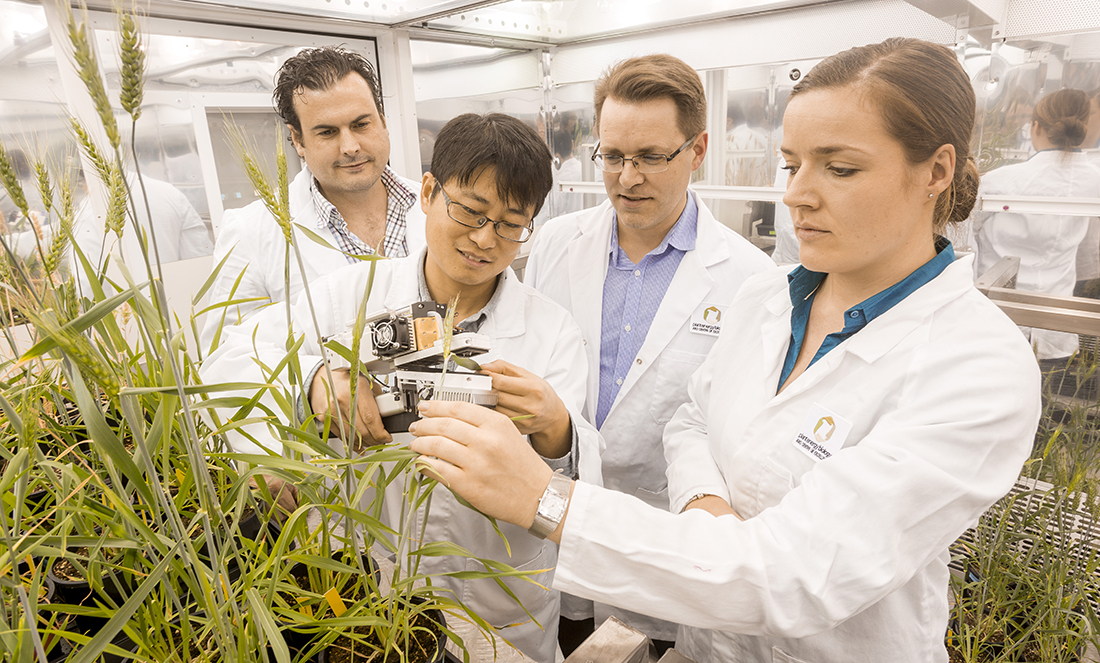

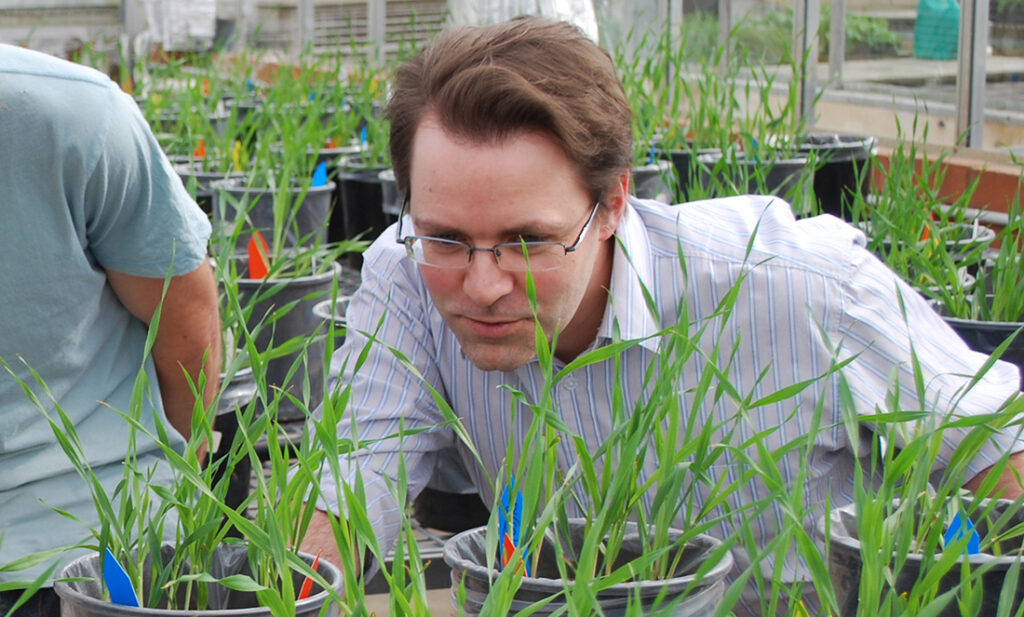

A lot of the work PEB does revolves around improving the energy efficiency of plants.

Plants take in energy from the Sun and turn it into the food we eat. If we can find a way for them to be more efficient at that, it could help them survive under less ideal conditions.

“We’re trying to understand the basic components of how … energy efficiency works in plants and then utilise it to change the way that the plants interact with their environment and what they can produce,” Harvey says.

“Our role has largely been finding the genes and suites of genes that are important for how plants respond to the environment, how they cope with harsh conditions.”

Once the genes are identified for something like drought or frost resilience, plants can be bred to survive better in low rain or cold conditions.

But there’s more we can breed plants for than just surviving on Sun-scorched plains or through freezing cold nights. PEB also works to identify genes for traits that make plants more profitable.

For example, the protein content of wheat can make it more or less profitable. Higher nutrient content in grains can increase interest in markets needing the health boost. Even in well nourished countries, boosting certain oils in plants that are linked to health benefits can make them more profitable.

“These are all potential areas where modifications can be made that benefit different groups and bring profits to farmers,” says Harvey.

Working together

Finding genes for traits is only the first part of a larger puzzle. PEB then needs to forward the information to people who can breed plants to have those genes. Then the plants must be tested in an actual farming situation.

There are many people and groups involved in turning the idea into a real change in industry.

Harvey likens it to the pharmaceutical industry.

“The pharmaceutical industry comes up with lots of leads, lots of ideas of new drugs that could be beneficial,” explains Harvey.

“They go through a whole series of different trials, and then at the end of that you might have a few products that come out that are widely used.”

A bright future

There are many opportunities for the future of Australian agriculture. If we continue to research and advance our knowledge in plant energy efficiency, our future could be very bright.

Harvey says one of the biggest opportunities lies in making food to export rather than just exporting grains.

“There’s an awful lot of profit for the country in actually taking those primary products and … making food … and exporting that,” he says,

“so making Australia an exporter of food rather than an exporter of primary commodities.”

It seems Australia will have a large role to play in global food security.

Thanks to the hard work of plant researchers, breeders and farmers, Australia won’t just be able to grow more food, we’ll be growing better food. This food, from our land down under, could be the way we feed the world in the future.