Cerebellar ataxia is a rare neurodegenerative condition that causes people to slur their words and lose their overall coordination and balance – giving the impression that they’ve had too much to drink.

It usually develops when people are around 40 years old, stopping them from working and living the life they once had.

There is currently no cure and no treatment. Patients use aids such as crutches and wheelchairs to stop them from falling and keep them steady.

What is ataxia? | Johns Hopkins Medicine via YouTube

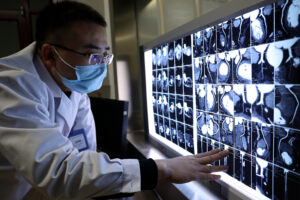

Although around 70% of patients with late-onset cerebellar ataxia remain without a genetic diagnosis, geneticists have recently discovered the genetic mutation responsible for 15% of cases.

“This really is a big find,” says Associate Professor Gina Ravenscroft from the Harry Perkins Institute of Medical Research who led the Perth arm of the international study.

“It has significant implications for people who are living with this disease, and we are excited to share it with them. They now know what has caused their ataxia and will be able to make plans for the future.”

An international effort

The study began in French Canada when neurologist Dr Bernard Brais discovered a high proportion of French Canadians with the disease had a genetic mutation.

The mutation is similar to the type that triggers Huntington’s disease.

“Dr Brais tested large families in Montreal to map which part of the genome had the mutation,” says Gina.

“He thought it was a new genetic cause of the disease that was possibly unique to French Canada. So he asked us to check our samples.”

The team in Perth already had samples from a cohort of patients with ataxia so they were able to test them quickly.

Dr Brais had spent a year with the Perth group, on sabbatical, as a visiting professor supported by the Raine Medical Research Foundation in 2007. The groups have worked together since then.

“We worked with researchers in Canada, the UK, India and Germany, and our results showed the implications are much more wide-ranging and the mutation is present in other populations.”

Looking forward

This discovery will help to inform patients on reproductive issues as well as how best to manage their symptoms.

“If you have the mutation, you have a 50% chance of passing on the mutation to your children. You can choose to screen the embryo to ensure it hasn’t got the mutation.”

Now that the mutation has been discovered, Gina and her colleagues are working with pathology laboratory Pathwest and international colleagues to screen and collect the data of hundreds of existing patients around the world.

“We are excited to be able to support people with this life-changing disease by giving them better advice on what’s ahead and how to manage their symptoms,” says Gina.

“The discovery will also inform the design of potential therapies and hopefully enable the development of effective treatment in the future.”