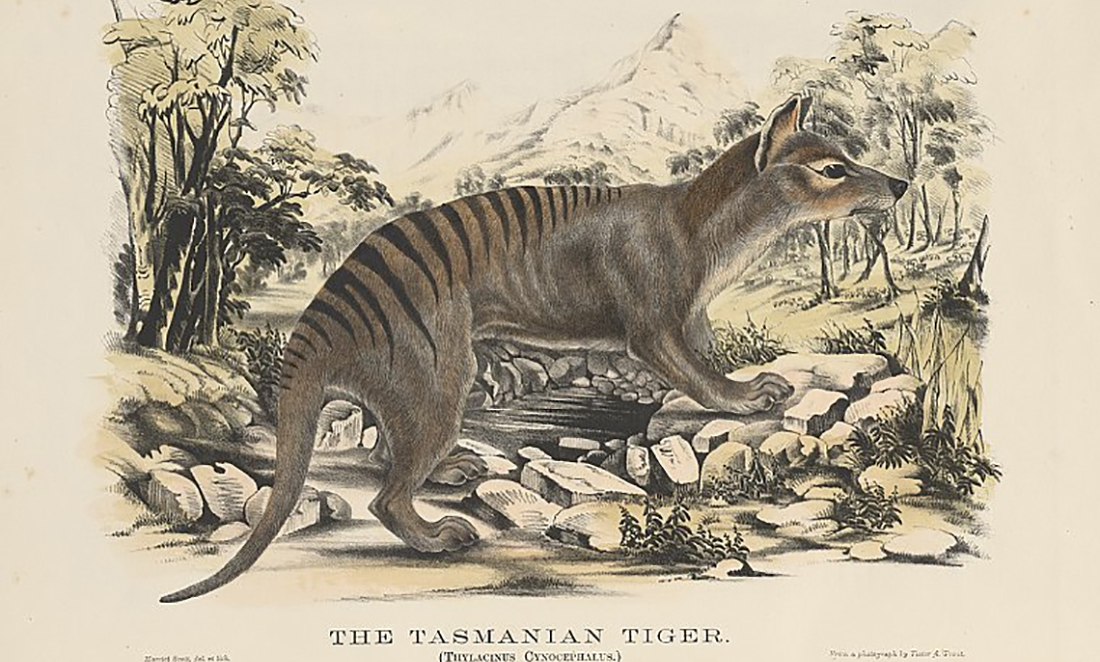

Whether you’re looking for a Tasmanian tiger, thylacine, Tasmanian wolf, marsupial wolf or even ‘Old Stripey‘, Thylacinus cynocephalus is truly a modern-day mystery.

No matter what you call it, the Tasmanian tiger is not a mythical creature. It was alive and well some 3000 years ago, until a heady combination of climate change, humans and dogs drove it to extinction.

These wolf-sized marsupials were carnivorous, carried their young in a pouch and had tiger-like stripes on their backs. Their jaws could produce an amazing 120° gape. And the origins of this species go back millions of years.

Thylacine 101

According to the fossil record, T. cynocephalus lived in mainland Australia and New Guinea about 2.5 million years ago and was not alone in its family tree. Over the past 20 million years, other species related to thylacines have roamed Australia and New Guinea.

“The genus Thylacinus as a whole has probably been around for about 20 million years or so,” says Dr Douglass Rovinsky, a Melbourne-based biologist who specialises in thylacine evolution.

“The earliest known, Thylacinus macknessi, was recovered from deposits up in Riversleigh that are probably 16–19 million years old, give or take a bit,” he adds.

“Over that period of time, there were at least four other species that came and went. Between 3–8 million years ago, we had three species of Thylacinus, and it’s possible (though totally unknown!) that they might have overlapped in time.”

Unfortunately, fossils of these thylacine relatives are rare. Not much is known about where they lived or for how long. What the fossil record does show is that, at some point, most of these thylacine species disappeared.

Only one survived.

“At the very latest, after 2.6 million years ago, we do not see any other species except for the thylacine T. cynocephalus – the others had gone extinct by then. And certainly, by the time that humans arrived, there was only the thylacine,” Douglass says.

The surviving species, the Tasmanian tiger, lived in mainland New Guinea, Australia and Tasmania. Evidence for their existence comes from a handful of confirmed fossils as well as Indigenous Australian rock paintings depicting the enigmatic animal. One desiccated carcass, found in 1966 in a cave west of Eucla on the Nullarbor Plain, suggested that the animal was once found in WA – more than 4000 years ago.

The last known living specimen died tragically in 1936 at the Beaumaris Zoo in Hobart. His name was Benjamin.

Wanting to believe

Over the past decades, there have been multiple sightings of thylacines, with no evidence but fervent belief.

“It’s a little bit like The X-Files – people want to be believe and this sometimes clouds judgement. I also see this a lot with the number of enquiries I get about general palaeontology from the public,” says Dr Gilbert Price, a Senior Lecturer in Palaeontology at The University of Queensland.

“People often find stuff and identify it as a dinosaur bone or egg or something equally exciting and bring it to me for confirmation – 99% of the time it’s just a rock that doesn’t look even remotely like the object they think it is.”

The Thylacine Research Unit currently hosts a list some 20 thylacine sightings from across Australia. Few include pictures or videos of the animal.

In the past few years, some of these sightings have made it into the media. In 2017, a seasoned thylacine hunter released a video from a reported Tasmanian tiger sighting in Hobart. It is much too far away to show any detail. “I don’t think it’s a thylacine … I know it’s a thylacine,” he declared.

In June 2018, a Sydney local claimed to have captured a thylacine with his home surveillance camera. Then, in 2019, a farmer from Victoria claimed to have photographed a thylacine near Clifton Springs. Neither offer a whole lot of detail.

The truth is out there – maybe

From a paleontological perspective, the fossil record shows no evidence of thylacines in mainland Australia for thousands of years. Experts think they disappeared in part due to human activity and in part due to climate change.

“They seem to drop out of the fossil record in mainland Australia and New Guinea when dogs were introduced and human population densities increased. This may also have coincided with a period of more intense El Niño activity. This happened 3–4 thousand years ago,” Gilbert says.

So could the Tasmanian tiger still be out there, somewhere? Maybe, but it is highly unlikely.

“For the thylacine to still be extant, you’d ideally want an ecosystem with few or no humans around and ideally no or few dogs. This could be remote areas of Tasmania or highlands of New Guinea. But even then, I wouldn’t hold my breath,” says Gilbert.

“It would be extraordinary for a land animal the size of a thylacine to still be out there undetected.”