On 18 July 2023, 97 pilot whales became stranded near Albany, WA.

It didn’t take long for hundreds of people to rush to Cheynes Beach and offer their help.

Despite the combined efforts of wildlife experts and volunteers, all the whales died.

The only solace for distraught witnesses is the hope of learning something from the tragedy.

FISHING FOR CLUES

Scientists currently don’t know why whales beach themselves in large numbers.

“It’s been a question for us for so many years,” says Dr Chong Wei, Research Associate at Curtin University’s Centre for Marine Science and Technology.

Scientists from across Australia are examining the pilot whale carcasses in Albany for clues.

“We’ve got a big team working on it,” says Chong.

A WA Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA) spokesperson says the tests may take several months to complete.

IT’S GETTING LOUD IN HERE

One theory behind the cause of whale strandings is acoustic trauma.

“Toothed whales rely on sound for major life functions,” says Chong.

“They send out sounds and listen to echoes to detect and navigate the environment around them.”

Loud underwater noises – like military sonar – can potentially mess with the whales’ echolocation systems.

“Human activities could cause enormous interference,” says Chong.

“[The whales] might lose their direction, which could cause beachings.”

HOLY HEARING

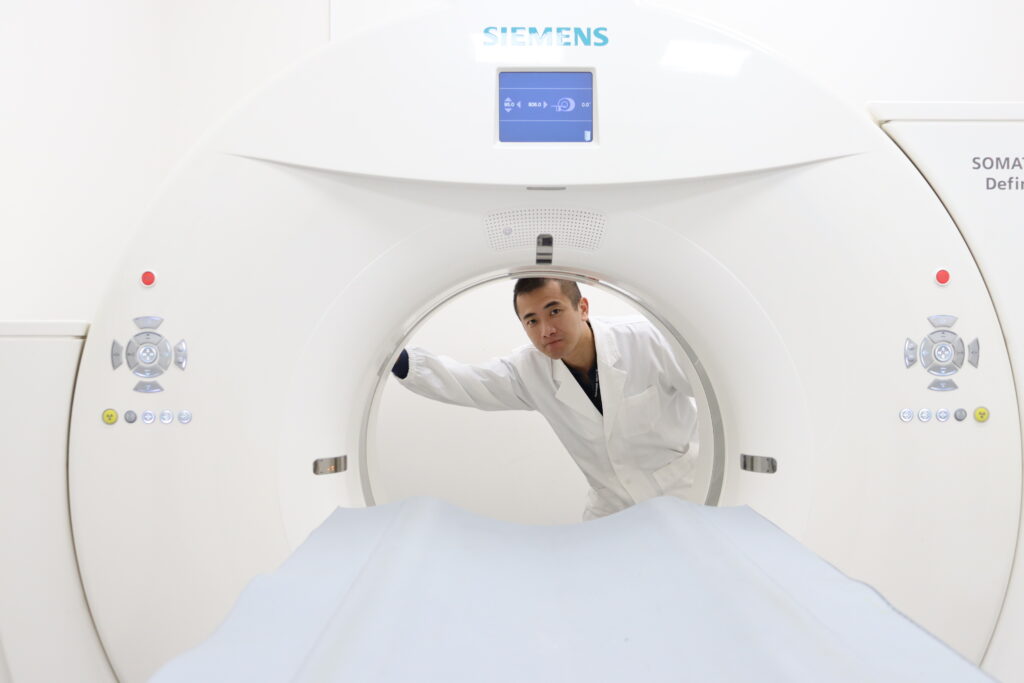

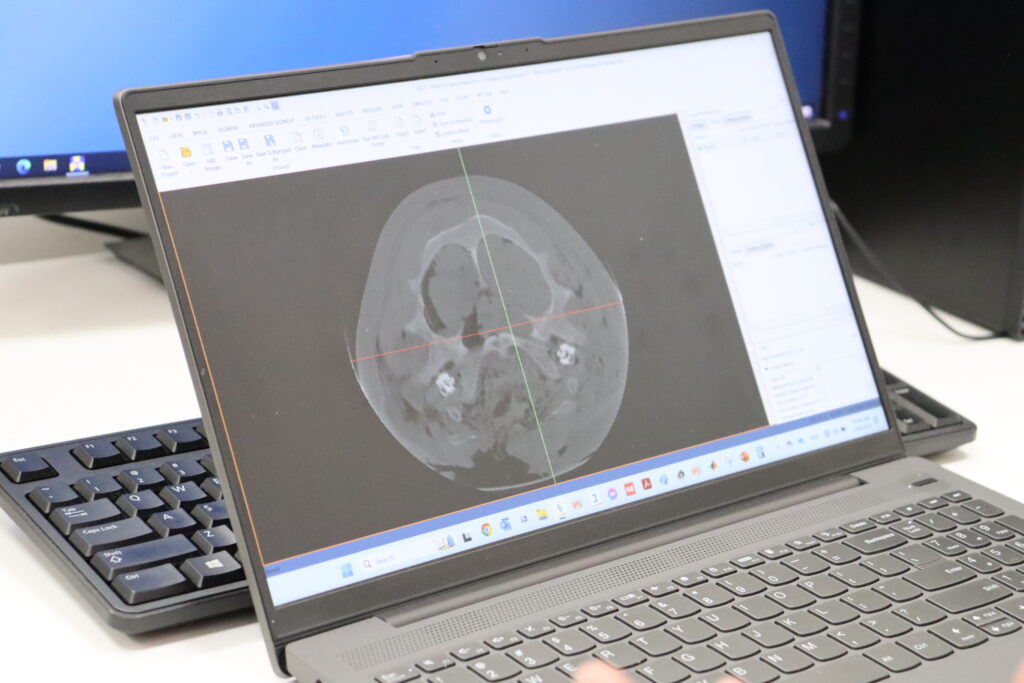

Chong’s team will search for evidence of acoustic trauma in the beached pilot whales via computed tomography (CT) scans of their heads.

His team has previously performed the same tests on fish to examine the damage caused by noise.

“When fish experience intense noise for a period of time, it will cause physical damage,” says Chong.

“Very tiny holes in the membranes of the otoliths can cause hearing loss.”

“First, we’ll do medical CT scans of the entire [whale] heads to check internal structures.”

“Then we’ll do micro CT scans of the ears to provide a much higher resolution.”

“Based on these scans, we can … simulate the sound production and reception processes that occur inside the animals’ heads.”

“Then we can assess whether noise could be a reason for the strandings.”

TESTING, TESTING

Disease is another theory behind mass whale strandings.

The Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development will run histopathology tests to check whale tissue samples for evidence of disease.

Flinders University in South Australia will test for viral or bacterial illnesses via dry swab samples.

The University of Western Australia will analyse DNA to “help understand population dynamics and potential genetic vulnerabilities”, according to the DBCA.

DBCA staff will also take morphometric measurements, including length, gender and photo IDs. It’s hoped that this will help us get a better understanding of the group’s composition and demographics.

DO THEY DO IT ON PORPOISE?

Some experts suggest whales’ strong social connections may be a contributing factor.

Group strandings tend to involve only the most social families of toothed whales. When one of their pod becomes stranded, others may follow.

Once beached, they may also refuse to leave their loved ones, hindering rescue efforts.

In an ABC interview about the pilot whales, Griffith University research fellow Olaf Meynecke said “It might just be that emotional connection to their peers that keeps them there.”

HOT SPOTS AND BOOBY TRAPS

Thousands of whale strandings occur every year.

New Zealand has recorded over 5000 strandings since 1840, while the UK has reported 17,850 strandings since 1990.

Whale stranding hotspots include Tasmania’s west coast, New Zealand’s Golden Bay and the United States’ Cape Cod.

Some of these sites share similarities in beach topography and environmental conditions. For example, Golden Bay and Cape Cod have a narrow land feature, long sloping beaches and large tidal variations.

It’s thought the whales’ echolocation systems may not work as effectively in these areas when the tide quickly recedes, effectively creating natural ‘whale traps’.

MAKING DATA WAVES

Records of whale strandings have increased in recent decades. However, it’s unclear whether this indicates a true increase in the frequency and scale of these events.

Instead, it may simply reflect improved human awareness and recording efforts.

“We’re certainly collecting more data these days,” says Chong.

In some cases, higher numbers of stranded whales could even suggest a growth in the total number of whales, indicating healthier populations.

Since commercial whaling ceased in the 1980s, humpback whale populations have significantly increased, along with reports of strandings.

ANIMAL WHALEFARE

Mass whale strandings are still largely considered a “natural phenomenon”, according to the DBCA.

Until we determine why they do it, it’s difficult to prevent.

On the plus side, strandings provide access to samples that are otherwise very difficult to collect.

This precious data can inform scientists about how the whales live as well as their possible causes of death.

Understanding them better can help inform conservation efforts.

“A lot of researchers from different research areas are busy working on this,” says Chong.