WA agriculture researchers have made it possible to watch five consecutive evenings of slug antics with time-lapse photography of canola crops.

The video offers a strangely mesmerising glimpse of life in a field as the slugs slowly devour a seedling over several nights.

LIGHTS, CAMERA, ACTION

Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (DPIRD) entomologist Svetlana Micic says the slimy critters were recorded with a waterproof smartphone attached to a post in a paddock.

“It just takes a photograph every 3 minutes,” she says. “From there, we can tell where the slugs or snails have moved.”

The team wrote programs specifically to track the pests, all of which will be made freely available at the end of the project.

EATEN ALIVE

Left unchecked, Svetlana says the pests can do a lot of damage to WA crops.

“If the snails or slugs are present when the canola’s being sown and they chew the growing point of the plant, the canola’s basically dead,” she says.

“If you look later on the season, slugs aren’t an issue once the crop is established, but snails can actually be a grain contaminant.

“Come harvest, what we’ve had in previous years is that snails have moved up into the head of grain—whether it’s cereal or canola—and then been incidentally harvested.”

Svetlana says the project is looking at ways to map slugs and snails in paddocks so farmers can bait where the pests are most prevalent.

“Instead of blanket baiting the paddock at one rate, hoping to kill the slugs or the snails, if you can find a way to map them, you can then change the bait rate or only bait infested areas,” she says.

“Where the slugs are densest, increased baiting rates may be appropriate.

“Where there are fewer slugs or fewer snails, you can a lower baiting rate or choose not to bait at all if the densities are less than threshold levels.”

DPIRD suggests farmers should bait at thresholds ranging between one or two and 40 slugs or snails per square metre, depending on the pest species and crop.

FIGHTING PESTS WITH TECHNOLOGY

As hypnotic as watching slugs and snails is, another part of the project is writing computer algorithms to spot the snails automatically.

If snails can be detected at the point they enter the harvest bin—where the grain is first dumped after being cut from the field—it could tell farmers where the pests are concentrated.

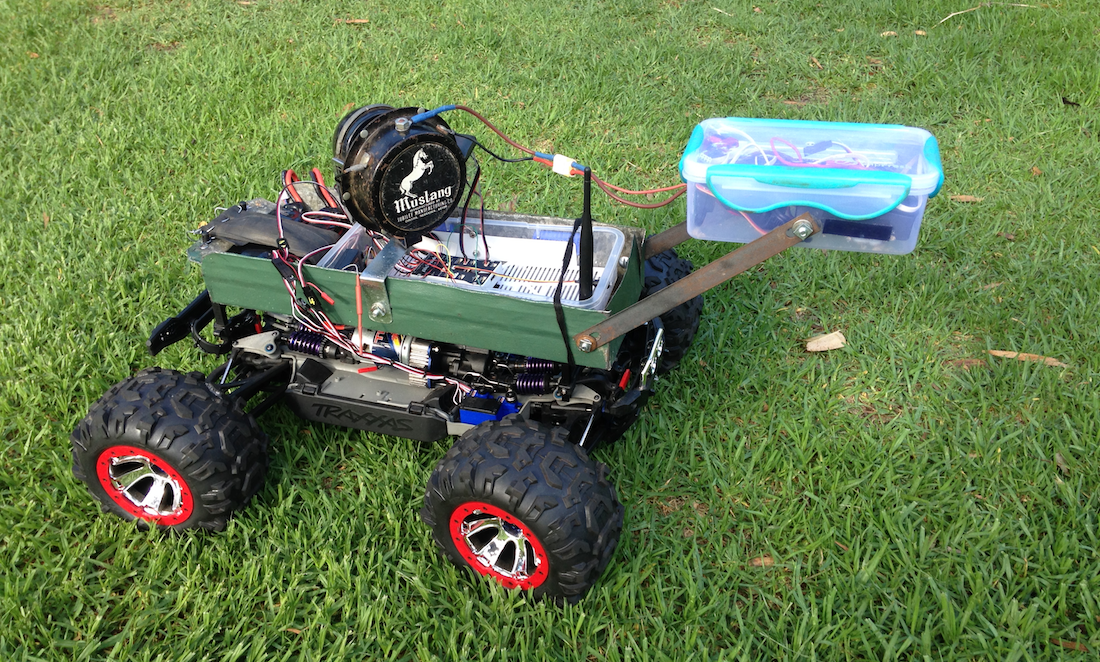

The team has also been trialling a smartphone attached to a small, unmanned roving vehicle, modified by DPIRD senior researcher John Moore to monitor slugs and snails at night when they are most active.

“It’s an ATV that’s been programmed so it can move autonomously down a paddock, stopping at set points and taking photographs,” Svetlana says.

Finally, the team is examining the climatic conditions that cause snails to move to the head of the grain, meaning farmers could avoid snail contamination by harvesting at certain times.

“Snails tend to move quite a bit,” Svetlana says.

“When it’s moist, they tend to stay lower down in the crop canopy, and as it dries out, they move up into the crop canopy.”

The research is part of the Boosting Grains Research and Development Flagship.