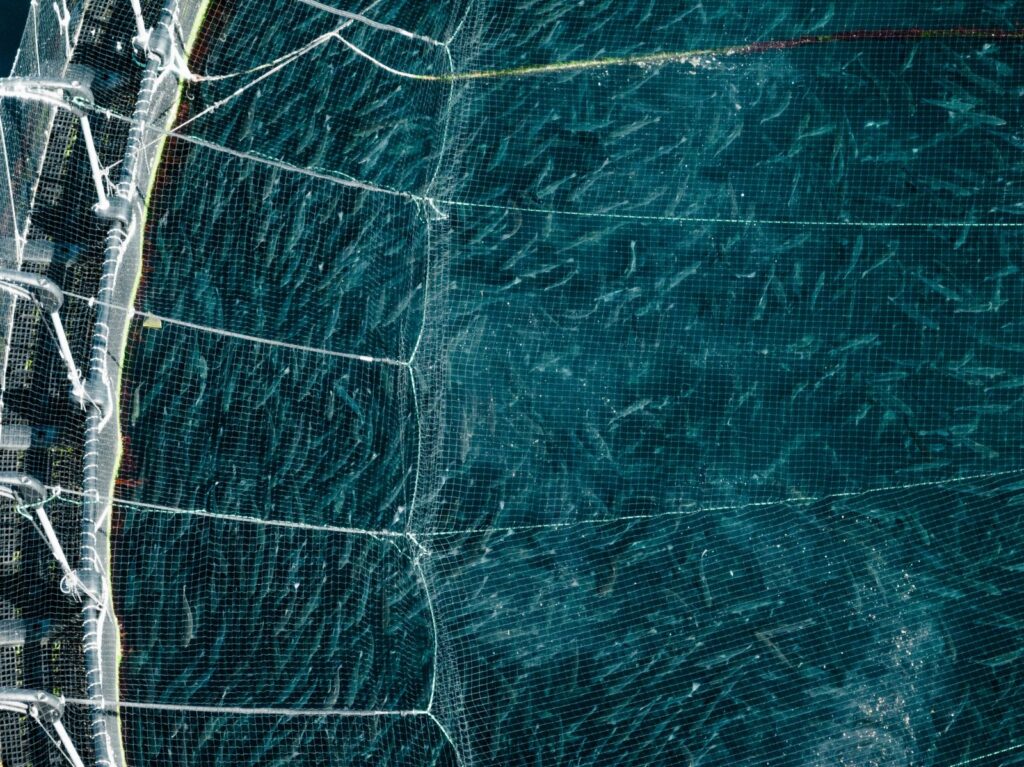

Bodies piled up against the edge of the pen, skin flaking off, pink flesh to the sky. From above, a glut of dead fish ripples in time with the waves.

This is the scene of a marine horror film – each body an expired Atlantic salmon.

It was filmed in Tasmania’s D’Entrecasteaux Channel by the Bob Brown Foundation, an environmental advocacy group.

It’s here that salmon are enclosed within gigantic steel pens – farms for major aquaculture corporations Tassal and Huon.

“We put the drone up and we just came across pens with hundreds and hundreds of fish floating on the top,” says Alistair Allan, an Antarctic and marine campaigner with the Foundation.

“There were just dead fish everywhere.”

The dead salmon had fallen to a bacterial infection that spread like wildfire through the population. An estimated 8% of the industry’s annual production died within weeks.

The impact of the deaths reached all the way to shore, with chunks of salmon fat washing up on nearby beaches.

The uncomfortable scenes, just ahead of an election, were met with anger and grief by advocacy groups and concern from the salmon industry.

“We will of course be reviewing every element of this event and will make changes to protect our fish, our environment, our workers and our communities into the future,” said industry body Salmon Tasmania in a fact sheet in response to questions from Particle.

And it put salmon farming, which has exploded in size and scale in Tasmania since it began in the 1980s, back in the spotlight.

Credit: Abolish Salmon Farming

BIG FARMER

Humans have been catching and eating fish for thousands of years, but it’s around the last 60 years where we’ve been farming salmonids at scale. Salmonids, which include Atlantic and Pacific salmon and rainbow trout, are among the most farmed fish species on Earth.

Salmon start their life in freshwater streams as tiny spawn, then migrate to the open ocean about a year into their life.

They spend the next 3–5 years maturing at sea, before returning to the place they were born to reproduce. (Most die because the journey home is taxing – swimming upstream for miles and dodging grizzly bears.)

Salmon are farmed in a way that attempts to mimic this cycle. The young are reared in huge on-land facilities, from plastic trays to giant tanks, where they grow until they’re ready to be transported to pens in the open ocean.

Credit: Wilderness Witness

They grow in these pens until they are ready to be harvested – a process that can take a few years.

It’s here, exposed to seawater and in constant exchange with the natural environment, where salmon farming has its greatest impacts.

SOMETHING IS FISHY

Wild Atlantic salmon are native to the Atlantic Ocean. No wild populations exist in Tasmania.

But in Norway, where salmon farming originated, locals have been fishing for salmon for hundreds of years. And farming could jeopardise the wild population.

“Salmon farming is the biggest threat to wild salmon in Norway, in addition to climate change,” says Eva Thorstad, a salmonid biologist at the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research.

Farmed salmon live in high densities, where there can be more issues with disease. If a farmed fish has sea lice and a wild fish swims past, disease or parasites could be spread.

Interbreeding can also be a problem. “Wild salmon are adapted to one river,” says Eva.

She explains that, if salmon escape, there’s a possibility they breed with wild salmon, which alters the genetic diversity, and adaptations to individual rivers may be lost.

In Tasmania’s Macquarie Harbour, research suggests salmon farming has contributed to lower oxygen levels in the water. The harbour is also the only remaining habitat for the Maugean skate, a critically endangered ray, and salmon farming jeopardises its existence.

FACTORIES OR FARMS

Overfishing has led to declines in many fish species. As the demand for seafood rose, so did the desire to implement farming and aquaculture. Since 2013, seafood production has been dominated by those methods.

The seafood industry is massive. It’s worth almost $400 billion per year.

Salmon – particularly Atlantic salmon – is big business, and the fish are farmed in places like Norway, Chile, Canada, the UK and Tasmania.

According to the Department of Natural Resources and Environment Tasmania, Tasmanian salmon aquaculture is an important contributor to the state’s economy and to the overall Australian seafood market.

Credit: Bob Brown Foundation

The Department also suggests the state supplies over 90% of Australian Atlantic salmon production, valuing the industry’s output at over $1 billion.

It’s at this intersection of industry and environment where conflict often arises.

As salmon farmers have scaled up production, environmental groups have also rallied against fish farming, which was once seen as a greener alternative to catching wild fish.

Alistair from the Bob Brown Foundation likens the scale of salmon farming in Tasmania to “factory farms out on the water”.

He’s concerned that aquaculture and farming have been touted as a fix for overfishing, but in reality, they’re doing severe damage to marine ecosystems.

SHOULD WE EAT FARMED SALMON?

If you’re a fan of sushi and sashimi, all of this might have you questioning your salmon intake.

First, some good news: The recent bacterial outbreak in Tasmania is not a risk to humans. The Department states, “P. salmonis is a fish pathogen and does not cause human or terrestrial animal disease, or any food safety risk.”

But farmed Atlantic salmon does account for the vast majority of salmon that reaches consumers’ plates, so it’s likely your sake maki has come from a farm.

That might not be a bad thing, depending on where the salmon comes from.

Norwegian farmed salmon is one of the most sustainable animal protein sources around, according to the Norwegian Seafood Council. The gains in sustainability have largely been driven by technological innovations and improving the supply chain.

Credit: Ivan Samkov via Pexels

Those concerned about environmental impacts may look to eat farmed salmon with certifications from global industry bodies such as the Aquaculture Stewardship Council.

However, even that has problems. Some certifiers have been accused of using underhanded tactics to remain certified, according to the Sustainable Restaurant Association.

“In my eyes, you can’t farm Atlantic salmon sustainably,” says Alistair.

For Eva, who has seen the impacts of salmon farming on wild fish, we have the knowledge to improve farming and regulatory changes would help protect the environment.

“I would say this is on the table of politicians to solve the problems.”