On WA’s largest island, one of Australia’s most successful restoration projects is winding back the clock more than 400 years.

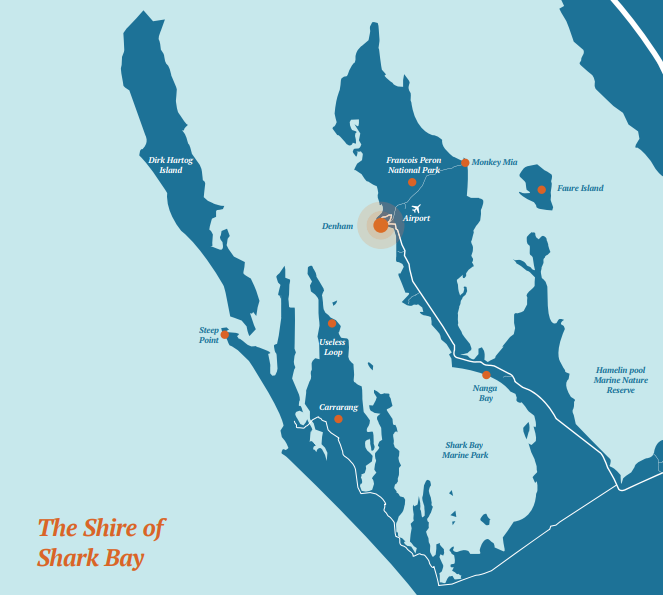

Wirruwana/Dirk Hartog Island lies just off the coast of Gathaaguda/Shark Bay within the Shark Bay World Heritage Area.

It’s a haven for small native mammals and reptiles, and is one of the world’s most important islands for mammal conservation.

Wirruwana hasn’t always looked like this though. It’s taken decades to return the island to the year 1616, and the work isn’t over yet.

PRE-1616

The Return to 1616 project was set up by the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA) and is funded largely by the Gorgon Barrow Island Net Conservation Benefits Fund.

The project takes its name from the year Dutch explorers arrived on the island. Its aim is to return Wirruwana to what it looked like before European influence.

Wendy Payne is the community engagement officer for the Return to 1616 project.

She says there is plenty of evidence about what the island looked like back then, particularly in the explorers’ journals and subfossil remains of animals that once inhabited Wirruwana.

“There were no weeds, there were no introduced feral pest animals to Australia…the island was pristine,” says Wendy.

Caption: Location of Wirruwana in relation to Gutharraguda and other prominent areas of Malgana Country.

A BAAAD MOVE

It wasn’t long before Wirruwana became Dirk Hartog Island and a pastoral station, in the 1860s.

“Probably one of the biggest impacts on the native vegetation was the grazing of introduced sheep,” says Wendy.

When the lighthouse was built in 1908, the lighthouse keeper brought goats to the island to provide milk and meat.

Credit: via Dirk Hartog Island (DHI_LR)

Sheep and goats had a devastating impact on the native wildlife.

“Once you’ve got some grazing herbivores that aren’t naturally in balance with the environment, they’re going to start removing vegetation,” says Wendy.

Once vegetation was removed, native animals lost their shelter and food and were at higher risk of predation.

Aside from the agricultural impacts, Wendy says “you’ve got people coming and going the entire time…and the one thing that usually goes with people is cats.”

Feral cat populations can quickly proliferate and their predation has a direct impact on Australia’s native mammals, birds and reptiles.

Without food and shelter, 10 of the 13 native mammal species were wiped out.

Wendy says if black rats, rabbits or foxes had made it to the island, their job would have been three times harder.

Caption: Cape Inscription and lighthouse

RARE SPECIES

Return to 1616 kicked into gear in 2009, when the State Government purchased the newly expired pastoral lease.

Wirruwana was granted national park status the same year.

Islands are generally easier to rewild than the mainland, because they have a natural border.

While there’s a number of non-government organisations who have established fenced reserves on the mainland to conserve and rebuild Australia’s ecosystems, Wendy says island rewilding can be more secure than on the mainland.

“A lot of the animals that DBCA has reestablished on the island are extinct on the mainland outside of fenced reserves,” says Wendy. “That’s how rare these animals are.”

TIME TRAVEL

To completely restore an island to what it looked like over 400 years ago is a challenge.

“It’s not just about re-establishing native animals on the island,” says Wendy.

“It’s also about managing…and eradicating weeds. There is a biosecurity management plan…to prevent new [weed] introductions.”

The team started by removing the sheep and goats. Then they radio-tracked female goats to find more goats, and removed those animals from the island.

The last sheep were removed in 2016, and the last goats in 2017.

“The one thing that’s truly remarkable in all of this is actually feral cat removal,” says Wendy.

“This is…the largest island eradication in the world at this point of feral goats, sheep and feral cats.”

Credit: via Shark Bay World Heritage

Using standard techniques, researchers managed to remove feral cats from Wirruwana.

To ensure the job was complete, they brought in sniffer dogs and walked all over the 80 km-long island for weeks until no cats were detected.

When feral cats were finally declared eradicated in 2018, more than 400 had been removed.

“I just can’t overemphasise what an amazing experience it is to see no… feral cat [tracks] on the island,” says Wendy.

A ‘STAGGERING’ CHANGE

Wendy says the difference between Dirk Hartog Island as a pastoral station and Wirruwana as a national park “is quite astonishingly different.”

To date, eight native species have been reestablished, and the team aims to have up to 13 animals reintroduced by 2030. With the return of the animals, the landscape is changing.

When you remove an animal from the environment, everything that animal does in its habitat, such as digging and distributing seeds, is lost.

Credit: Mark Cowan

With the return of native animals, these processes and Wirruwana are slowly being restored.

“The difference in just a few short years is really quite staggering,” says Wendy.

A REWILDING BLUEPRINT

Wendy says rewilding Wirruwana is one of the most important ecological restoration projects in Australia, and it’s highly regarded globally.

With impressive outcomes, what does it mean for the future of Australian environmental conservation?

Return to 1616 has shown what is possible. The project provides evidence – and inspiration – for rewilding other islands and protected environments.

Wirruwana can lead the way for others to follow in its footsteps, to create a blueprint for the conservation of Australia’s precious ecosystems.