If there’s one thing Australia is famous for it’s wanting to kill you. Sharks in the ocean, crocs in the river and the sun trying to grill you like a scotch fillet.

But of all Australia’s deadly denizens, the most infamous are our creeping, crawling, slithering, scuttling, biting, stinging venomous creatures.

Venom is a toxin that’s injected by a bite or sting, and it has two purposes: to attack prey and to defend from predators. But while all venoms might share a purpose, not all venoms are the same.

These toxic concoctions come in a variety of fatal flavours, each with its own charming way of un-aliving you. So let’s explore some of the ways that you might die on your next stroll through the WA wilderness.

HAEMOTOXINS (BLOOD VENOM)

The first variety of venom you might encounter is haemotoxins.

Literally ‘blood toxins’, haemotoxins attack the red blood cells and blood vessels of their unfortunate victims. This prevents oxygen from being carried to vital organs, and the same time, you begin bleeding internally. It’s quite bad for you.

In WA, this delightful toxin can be found in the venom of tiger snakes, one of the most common snakes in Australia. Yay.

MYOTOXINS (MUSCLE VENOM)

Next on the list are myotoxins. These are favoured by venom users with a ‘work-smarter-not-harder’ life philosophy. A myotoxin user may ask themselves why chase down your prey when you can simply stop their muscles from working at all?

Myotoxins break down muscle fibres near where the venom has been injected. No muscle, no moving. That means no running away for prey and no attacking for predators. Sometimes, the best plans really are the simplest.

These muscle-messing mixes can be found in WA’s resident mulga snakes. Also known as king brown snakes, it’s no wonder they have such a regally prudent approach to envenomation.

CARDIOTOXINS (HEART VENOM)

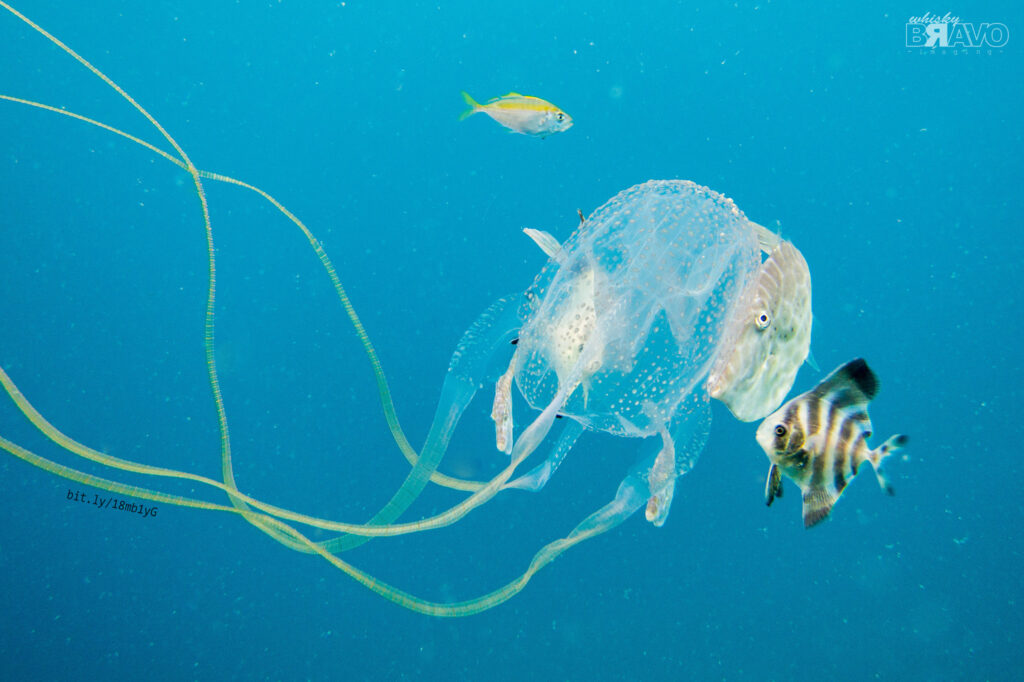

Cardiotoxins are a more exacting choice of venom. This discerning toxin doesn’t concern itself with attacking just any muscle. Cardiotoxins specifically break down the plasma and muscles of the heart. How heartbreaking.

This heartless venom is used by a surprisingly brainless WA marine predator, the box jellyfish. Fancy a swim?

NEUROTOXINS (NERVE VENOM)

Last on our list, but by no means least, are neurotoxins.

Fast and effective, neurotoxins attack the nervous system connecting our body to our brain. Without nerves, you can’t really do … anything. Neurotoxins prevent the brain from telling the body to move, feel, see, hear or even breathe.

Their effectiveness also seems to have made neurotoxins quite a popular choice among venom connoisseurs. In WA, neurotoxins are used by redback spiders, scorpions, cone snails, blue ringed octopuses, Irukandji and many types of snakes.

Now I’m feeling nervous.

NO NEED FOR CONCERN

If this list of venoms has made you feel uncomfortable, it’s worth remembering there’s a very good chance you’ll never be injected with any of them.

Instead, you might encounter one of the many, many types of venoms that aren’t on this list, like vasculotoxins, necrotoxins, coagulotoxins, cytotoxins or crinotoxins.

So don’t worry.