The word ‘asbestos’ elicits feelings of concern – or even fear – when we hear it.

Without knowing exactly what it is, most of us will say it’s Bad Stuff™.

But why is it so bad?

And why was something so dangerous so commonplace in Australian homes?

FIRE RESISTANCE

Asbestos is a group of six silicate minerals with fibrous crystals that can be woven into fabrics and other materials.

While asbestos fibres have many textile uses such as strengthening pottery, it is best known for its remarkable fire resistance.

Credit: Raimond Spekking CC BY-SA 4.0

Over thousands of years, this unsingeable material has been used to make:

- shrouds for cremating Greek kings

- flamboyant Persian party trick napkins

- unquenchable oil lamp wicks

- fire-proof tablecloths for clumsy Frenchmen

- Italian banknotes

- flaming trebuchet projectiles.

It is so impervious to fire that ancient Persian stories claimed it came from the fur of mythical fire-bathing salamanders.

Credit: Michel Maier, 1617

During the Industrial Revolution, asbestos started being used en masse.

Developers recognised its strength as a building material and the value of its resistance to chemicals, heat and electricity.

Industrial-scale asbestos mines popped up all over the world in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Australia became one of the highest producers and consumers of asbestos products.

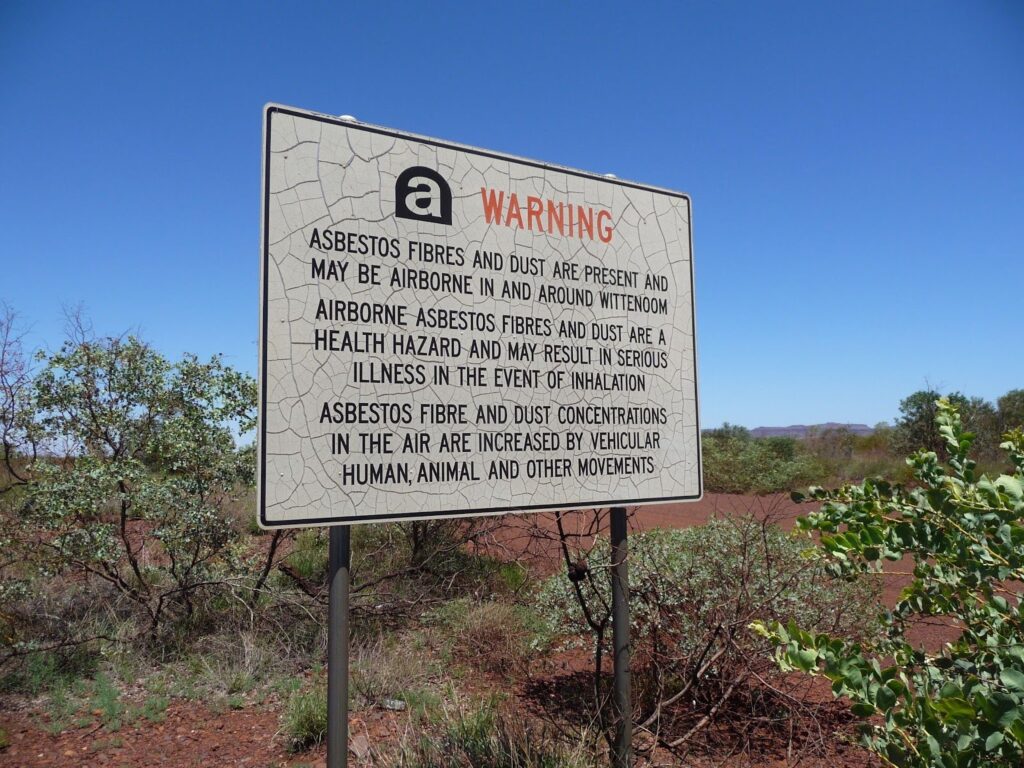

In the 1930s, the WA town of Wittenoom was one of the world’s largest asbestos mines.

DANGER IN THE AIR

The terrible human cost of this ‘wonder material’ was revealed over the course of the 20th century.

Mesothelioma, an extremely aggressive type of lung cancer, became rampant among people who had inhaled asbestos particles.

In Australia, the mining, production and use of asbestos products caused hundreds of thousands of deaths.

An estimated 4000 people still die from asbestos-related diseases like mesothelioma each year.

Credit: CC BY-SA 3.0

Despite Australian medical professionals recording the health impacts of asbestos as early as 1897 (not to mention the Romans figuring it out nearly 2000 years ago), little was done to protect Australian miners or construction workers until the 1960s.

Even then, asbestos products weren’t completely banned until 2003.

A LASTING LEGACY

It’s unclear why there was such a lengthy delay between the medical information becoming available and when legislation was put in place.

Did the multibillion dollar global asbestos industry have anything to do with it?

Even now, hundreds of DIYers are exposed to asbestos each year – not to mention that the once thriving town of Wittenoom is the largest contamination site in the southern hemisphere.

Credit: Five Years CC BY-SA 3.0

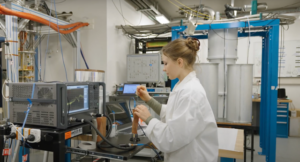

Asbestos has left a terrible legacy in Australia, but pioneering research is being done right here in WA to treat mesothelioma and other asbestos-related diseases.

WA Premier’s Student Scientist Award winner Nicola Principe’s research looks for ways to boost the body’s natural response to the cancer and complement existing chemotherapy treatments.

Hopefully, we are finally beginning to move beyond the impact of this fireproof poison.