If you were living in WA between 2011 and 2014, you would’ve heard the words “seven fatal shark attacks in three years” a lot. It was an emotive issue for a lot of people and, in true Jaws fashion, the solution often proposed was: kill the sharks.

Many scientists and shark experts were against the culling of sharks. Sharks have an important role to play in the ocean as an apex predator. Especially Great White Sharks, which are already vulnerable to extinction.

WA scientist and surfer, Craig Anderson, was able to see the issue from both sides. So he got together with his friend Hamish Jolly, an accountant and keen kiteboarder. The pair discussed the need for less invasive solutions for shark attacks. From there, the idea for their company, Shark Mitigation Systems (SMS), was born.

“With increasing personal anxiety surrounding our favourite hobbies, we began a journey to improve ways to mitigate the risk of a shark attack” Craig explains.

Now you see me, now you don’t

So how do you stop a shark attack? The first step for SMS was to better understand the visual systems of sharks.

“Given that humans are not naturally in the shark’s food chain, our initial instinct was that shark attacks on humans was based on mistaken identity,”

“With this thought, we funded research with the Ocean’s Institute at the University of Western Australia to determine exactly what large predators see under different light conditions”.

The research helped SMS create two patterns to visually deter sharks. They called them Shark Attack Mitigation Technologies or SAMS. The patterns have been integrated into wetsuits and surfboards. They also have the potential to be used for kayaks, water-skis and more.

The first pattern, Cryptic, camouflages the wearer in the water column. The second pattern, Warning, was designed for use on the water’s surface and changes the wearer’s silhouette that is projected from below.

Initial testing of the patterns has yielded positive results.

“UWA have been independently testing the patterns with wild animals since 2012 in various locations in Western Australia… and also in South Africa” Craig reveals.

“Results… have indicated up to a 400% increase in time to engagement with the SAMS disruptive colouring pattern in comparison to a black wetsuit”.

Smart Beaches

After the success of SAMS, the boys wanted to cast an even larger net (metaphorically speaking, of course). So they began looking at ways to provide safety on an even larger scale, such as an entire beach.

“Methods of protecting swimmers at a beach-scale have been unchanged for decades, and the current methods are producing negative impacts on marine life.”

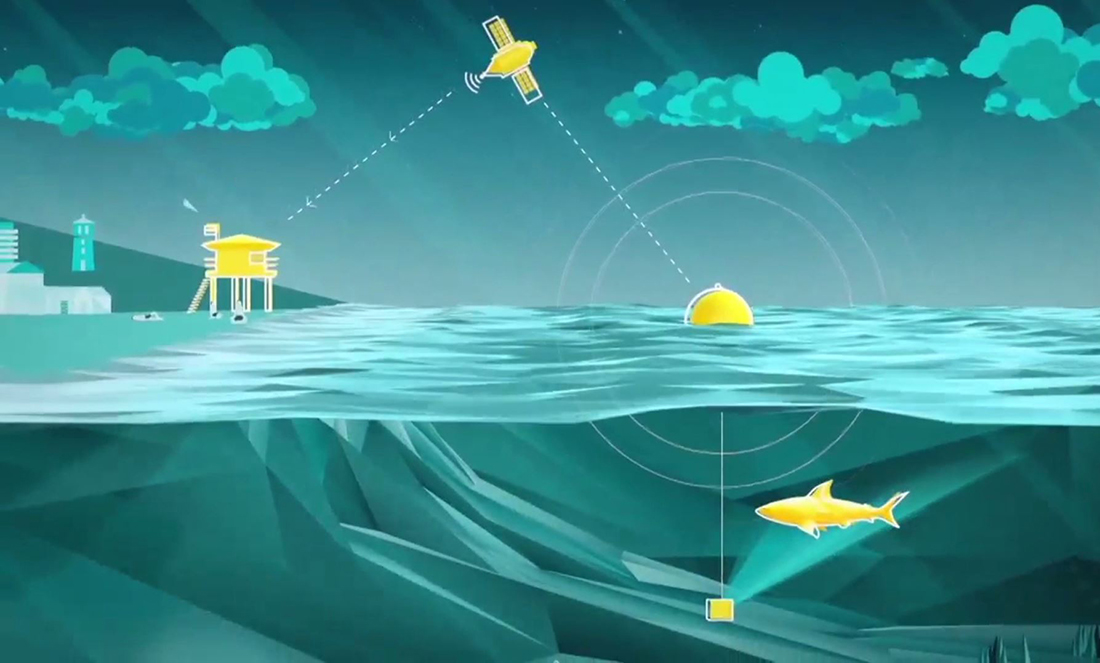

“With technological development in sonar hardware and visual recognition capabilities, we have developed a system that acts like a ‘virtual net’, without a physical barrier, which provides real-time information to lifeguards and authorities.”

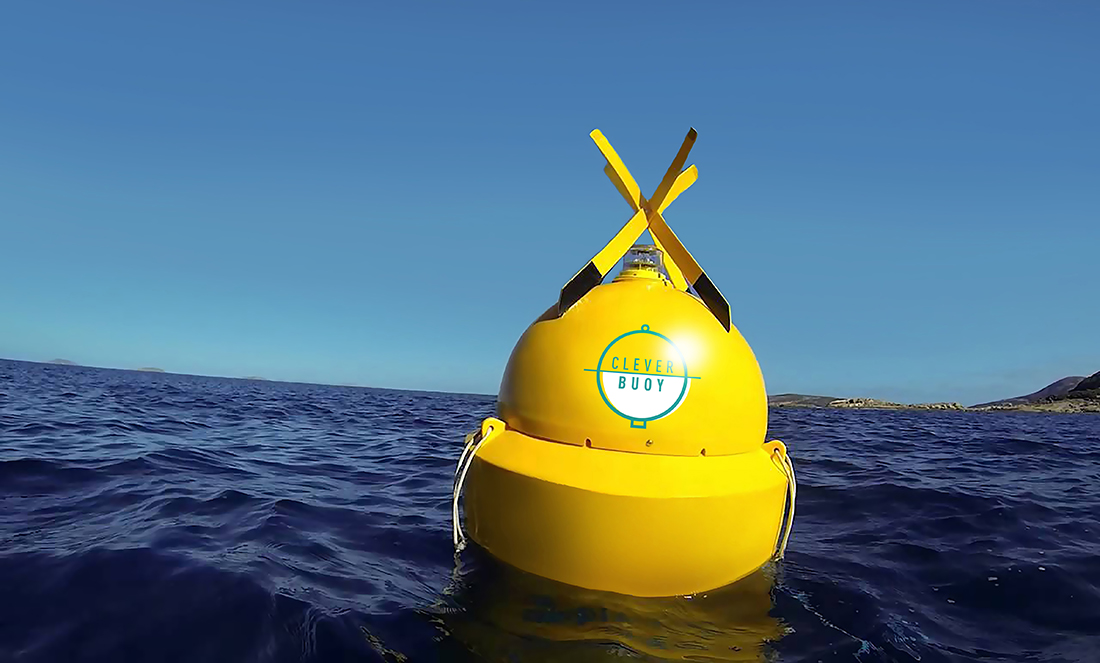

The system is Clever Buoy – a smart buoy which uses multi-beam sonar to look for moving objects in the ocean. Once it finds something, it ‘watches’ the way it swims to see whether it matches the swimming pattern of a shark. If it makes a match, it sends a message to lifeguards and authorities to warn a shark is nearby.

The Clever Buoy is currently enjoying a test-run at City Beach, following successful deployments at Bondi Beach and South Africa. The WA Government deployed two Clever Buoys to trial, as part of a larger effort to reduce shark attacks. The trial runs until April 2017, and if the buoys show promise, there could be more on the horizon.

“Various Government Departments… will be assessing the systems at the end of this trial and its application across other sites in WA.”

Why can’t we be friends?

Sharks aren’t as bad as scary movies, dramatic media reports and their toothy smiles make them out to be. Their notoriety shouldn’t overshadow their important role on top of the food chain. That’s why SMS sees the need for humans to share the oceans with sharks.

“Sharks are an apex predator in the ocean, and their survival and management is critical to the whole marine ecosystem,” Craig says.

“By using smart technology that is not only non-invasive but will provide valuable information on the identification, location and movement of these animals, [we] will greatly improve our knowledge to appropriately co-exist”.