We asked cultural guide Dr Noel Nannup and writer Kim Scott about science in the Noongar culture – an Aboriginal nation that spans Australia’s southwest, from modern Geraldton to Esperance.

“The way we divide knowledge in Western society is not like the way it happens in Aboriginal societies,” says Kim.

“If we’re just trying to bring in Indigenous content within a science frame, it gets us sort of ass-about in a way.

“You end up rather defensively talking about Unaipon and the shearing piece or the aerodynamics of the boomerang.

“Instead, we talk about Indigenous knowledge.”

So what is Indigenous knowledge?

“In Bill Gamage’s book The Biggest Estate on Earth, he talks about how people organised and shaped the whole landscape – Australia being the only continent with the biggest trees growing in the worst soils because they were managed.

“That and enabling people to predict what time to be at certain places for hunting or for luring resources, as well as fire management.

“There’s all sorts of techniques and science strategies being displayed.

“Tony Swain’s book A Place for Strangers articulates a place-based consciousness.”

What do you mean by this consciousness?

“Indigenous world views are intellectual approaches based on context and pattern,” says Kim.

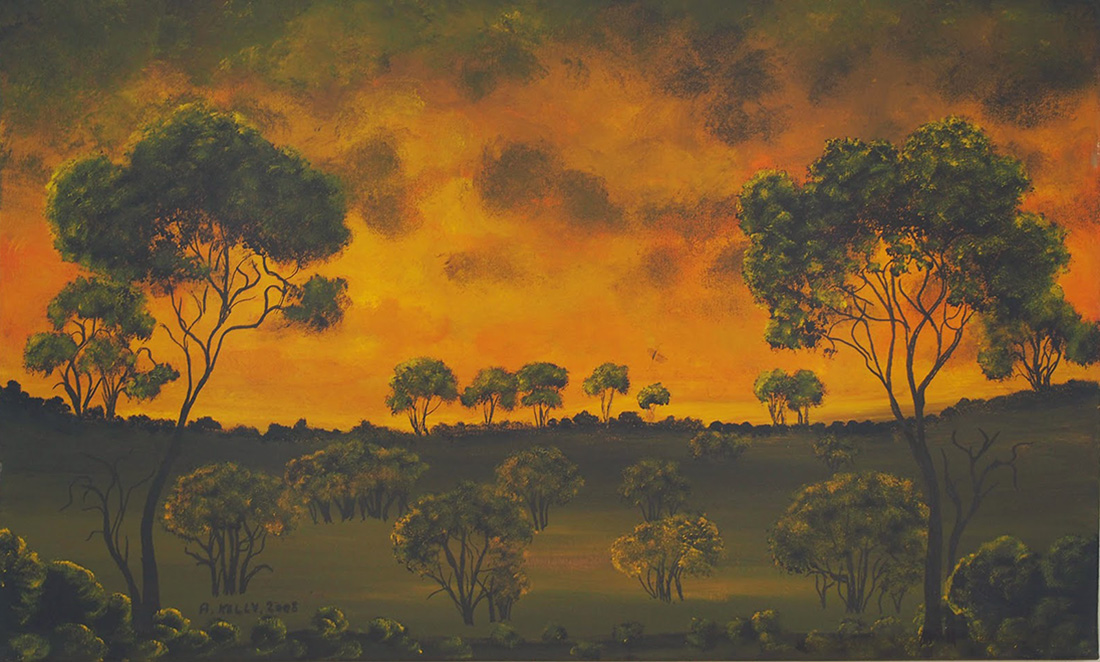

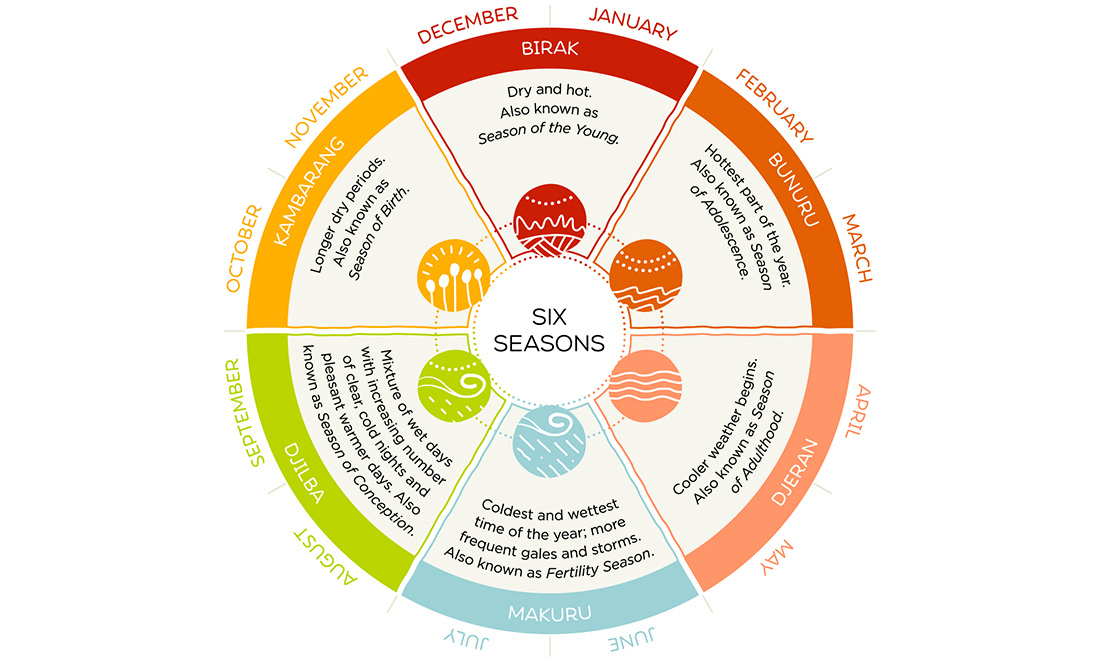

“The landscape has these fundamental rhythms of place: the lunar rhythms, harvesting, gestation and birth, pollination, blooming and harvest. There are different rhythms in a place that the stories and song lines indicate.

“Then time comes in. The now is an intersection of all those different rhythms of a place.”

“Time isn’t the major organising principle for Aboriginal societies, it’s place.”

“Nowhere is wilderness. The whole continent is shaped through Indigenous cultures.”

Noel adds, “What is wilderness? It means a place no one has ever been. A place of nothing. Every piece of our country has a story, song, dance and piece of art. Every square inch of it. So how can wilderness apply as a word here?”

How can modern Australia use Aboriginal knowledge?

“The system is so used to harvesting Aboriginal knowledge, and that will continue. They learn so much from us and make money from things we had already built,” says Noel.

“I’ll share a story called The Carers of Everything – that’s in English. In language, it’s Moondang-ak Kaaradjiny, which means the spirits that come out of the darkness into the light to care for everything.

“In the story, the spirits of the land – the trees and animals – made us the carers of everything. They would promise to help us however they could as long as we didn’t use them up until there were none left.

“All the way through that story is science. That science is firmly embedded in and woven with common sense.”

“Empowering Aboriginal people and letting them share their heritage gets over some of those impasses we have with appropriation,” says Kim.

“Aboriginal Australia has been pretty radically disempowered, and that’s part of the problem,” says Noel.

“The mob that came here had a book with 10 commandments. One was you shouldn’t steal. They don’t have a receipt for the land here. Another was you mustn’t kill, but our land is stained in Aboriginal people’s blood.”

So how do we fix this problem?

“Many of us are involved heavily in cultural recovery and decolonisation. That means looking at one’s own traditions versus others’, looking at loss and gain,” says Kim.

“We work with a group of kids through the Aurora Foundation. We have them for a week of school holidays every year. It’s such a moment of academic and cultural enrichment,” says Noel.

“We teach them memory codes, so they can go to school and do ATAR instead of every teacher having low expectations. These low expectations are entrenched in our education system. We’ve got to get our kids out of that.

“But what are the problems we have in Australia? We’ve got to tell the truth before we have an understanding with each other, otherwise everything we do is starting halfway up the ladder,” says Noel.

“Aboriginal Australia has been pretty radically disempowered, but there are people working towards cultural recovery. That includes preserving traditional knowledge but also it’s about healing and recovery for our people today,” says Kim.