A unique study that saw scientists light small fires in the Kimberley has found patches of unburnt grassland can help native animals recover after a blaze.

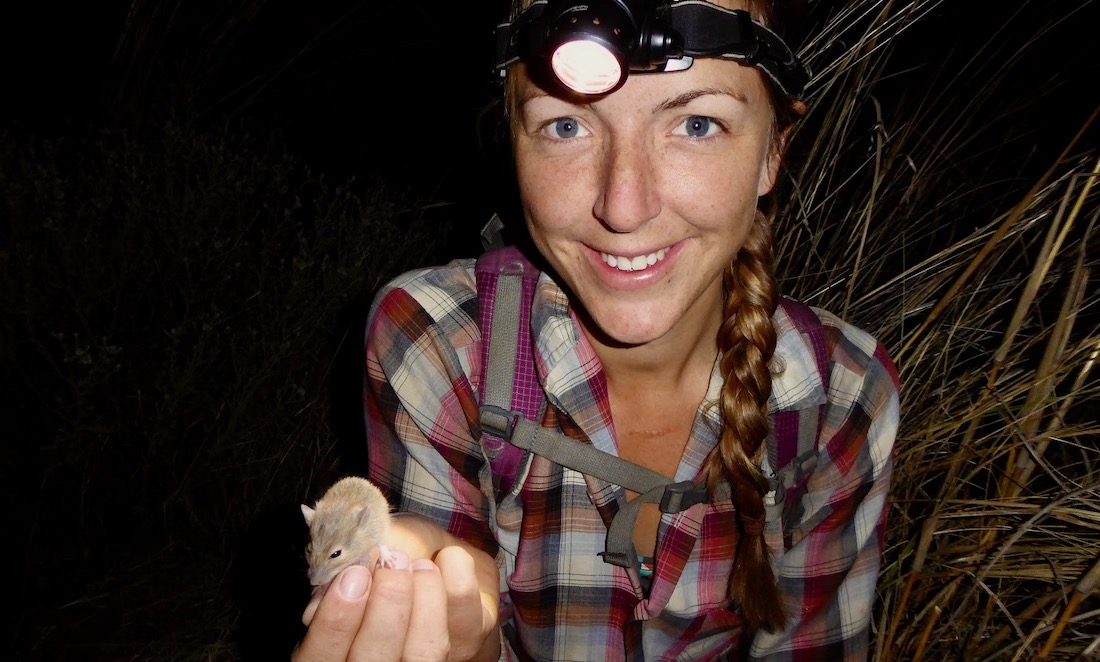

The research looked at the pale field rat, a small nocturnal mammal that lives in the grasslands of northern Australia.

It found ‘micro-refuges’ create a safe haven from which animals can recover after a fire.

Lighting fires

Murdoch University ecologist and geneticist Dr Robyn Shaw led the study as part of her PhD research at the Australian National University.

She says there aren’t many experimental field studies involving fires.

“That’s for obvious reasons, because doing a fire experiment can be really difficult and challenging,” Robyn says.

Luckily, Robyn had help from the Australian Wildlife Conservancy at the Mornington-Marion Downs sanctuary.

At almost 6000 square kilometres, the reserve is one of Australia’s largest privately owned protected areas.

The sanctuary is also subjected to regular prescribed burns – a practice Indigenous Australians have used to care for the landscape for thousands of years.

“Mornington’s really exciting because it is one of these places that has active fire management,” Robyn says.

“And so it is possible to do these field experiments on fire.”

Rat race

Before getting out the matches, Robyn spent 2 months trapping and microchipping pale field rats across the sanctuary.

(Apparently, the animals are big fans of peanut butter and oats.)

“We burnt in a patchy, mosaic way,” Robyn says, “at night, allowing things to burn themselves out so that there were some areas where there were patchy burns and then some areas where there was still vegetation remaining.”

The researchers also lit high-intensity fires designed to replicate a wildfire.

“That was really intensive burning,” Robyn says.

“We waited for a day where the winds were right so that the contained area would have all of the vegetation removed.”

Tracking survivors

A year after the fires, there was no difference in rat numbers in the control, patchy fire and wildfire areas.

But the microchips told a different story.

Robyn says some microchipped individuals survived the patchy management burns, but no rats survived the more-intense ‘wildfires’.

“What that shows is that, after fires, those animals within the unburnt patches can contribute to repopulating the site,” she says.

“Within our study, that wasn’t a problem, because it was over quite a small scale.

“But you can imagine if you’re looking at a really intense, large-scale fire … and you’re not having these refuge, unburnt patterns, then it’s going to take a long time for populations to recover.”

Seeds in the landscape

Robyn says good fire management practices can create long unburnt patches that act as refuges.

“A lot of the time, even in really intense wildfires, there are still areas that burn less intensively and where there is a little bit of remnant bushland,” she says.

“It’s just highlighting that we really need to think about making sure that those areas remain.”

Robyn is quick to point out that fire acts very differently in the grasslands of the Kimberley compared to WA’s South West.

“But I think it still applies that having refuges where animals survive is really important,” she says.

“We do need these … little seeds in the landscape where recovery can happen from.”