They can be found in the air we breathe, the water we drink and the food we eat. They can be found within our cells, our organs and even our brains.

Microplastics are playing a game of hide and seek, but by infiltrating almost every part of our lives and bodies, they’re making the seeker’s job pretty easy.

As their name suggests, microplastics are tiny pieces of plastic – leftover debris from the countless plastic items we use in our daily lives.

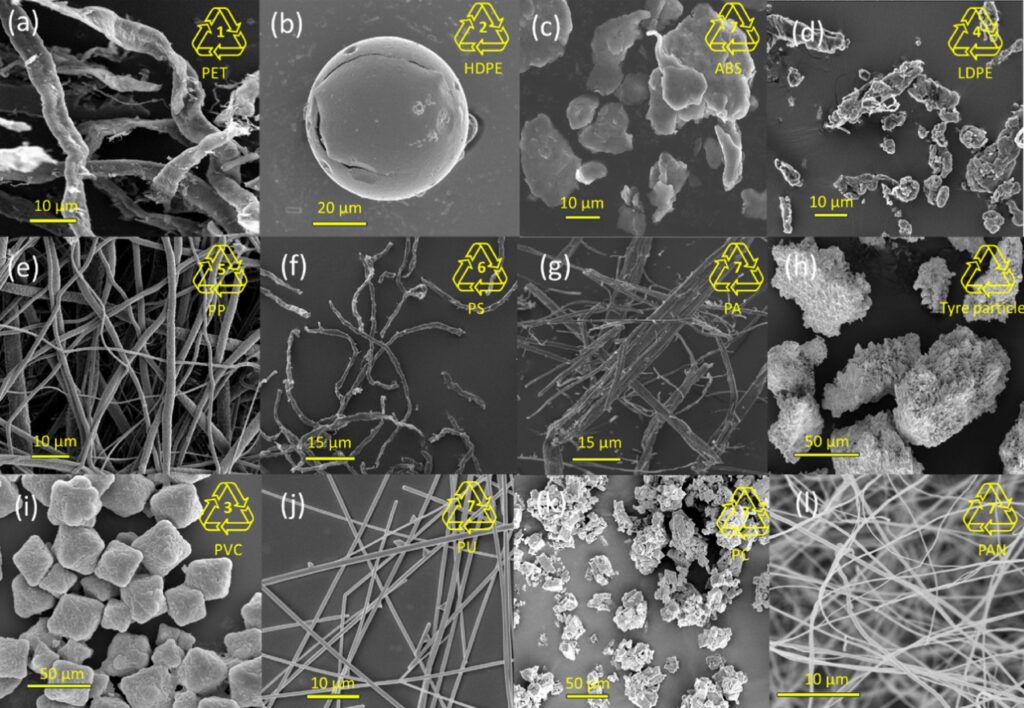

They come in many different shapes and are defined as smaller than 5mm in size. When they’re smaller than 1 micrometre, they’re also known as nanoplastics.

Microplastics can come from a range of sources, including trash. Rubbish from our homes and large-scale industrial processes all contribute to the production of microplastics that end up in our environment.

Every year, about 3 million tonnes of microplastics enter the environment. That’s over 8000 tonnes per day.

Credit: Hossain et al. 2024

WHERE DO THEY COME FROM, WHERE DO THEY GO?

Microplastics can enter our bodies through the air we breathe, through our skin or even when we brush our teeth or use other personal care products.

Another way we’re exposed to microplastics is through food. Seafood, poultry, honey and other food products have been known to contain microplastics.

Even storing or heating food in plastic containers can contaminate it with microplastics. One study led by the CSIRO found microplastics in Australian meat, rice, takeaway foods and even fresh fruits and vegetables.

Drinks aren’t safe either. Contaminated water is another major source of microplastics, including tap and bottled water. On average, a litre of bottled water has about 240,000 particles of microplastics.

Fancy a cup of tea instead? Tea bags come with a big serving of microplastics. One tea bag can release more than 1 billion microplastic particles.

THE PERTH TRIAL

Michaela Lucas is an immunologist at Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, Perth Children’s Hospital and a professor at UWA.

She is leading a new project called the PERTH Trial, which seeks to understand how much plastic is entering our bodies, where it is coming from and whether it’s affecting our health.

“Many of the plastics and plastic-associated chemicals get into our food from the food packaging and plastic kitchen utensils. Overall, the more processed food is, the more plastics it may contain,” says Michaela.

“The plastics we breathe in come from carpets, our clothing, plastic furniture and toys.

“Many plastic-associated chemicals are also in personal care products like some shower gels or lotions. These chemicals can be directly absorbed through the skin.”

Credit: UWA

A CAUSE FOR CONCERN?

Being so tiny, do you really need to worry about them? Probably.

Microplastics contain more than 16,000 different chemicals, including many known carcinogens and endocrine disruptors – chemicals that affect how our hormones work.

Studies using mice have consistently shown microplastics can have negative effects on different organs, including the intestines, lungs and liver, as well as different parts of the reproductive and nervous systems.

In humans, most studies in this area have focused on identifying microplastics in different parts of the body – and the findings are nothing short of Halloween-level scary.

Microplastics have been found in organs of the cardiovascular, digestive, endocrine, integumentary, lymphatic, respiratory, reproductive and urinary systems.

They have also been found in breastmilk, meconium (a baby’s first poo), semen, stool, sputum (lung mucus), urine and the brain.

THE MILLION-DOLLAR QUESTION

Can microplastics affect our health?

In short, we don’t know.

The WA Department of Health states: “Studies in human populations are however difficult, because; we are exposed to a wide-range of other environmental contaminants, we don’t know how much micro-plastic we are exposed to, and there are no specific plastic-related diseases.”

That’s not to say there hasn’t been significant research into this. For example, one study has linked microplastics to the risk of certain heart diseases.

The study focused on patients with a condition called carotid artery plaque, where plaque builds up in arteries. It found that patients who had microplastics in their plaque typically were more than four times more likely to have a heart attack than patients who did not have any plastics in their plaque.

It’s important to remember these results show correlation not causation. This means the study did not prove microplastics cause heart attacks but found that people with microplastics in their plaque tend to have a higher risk of heart attacks.

We don’t know for certain if microplastics are actually causing the attacks, as there may be other factors driving the observed correlation.

Credit: Hossain et al. 2024

A LIFE IN PLASTIC ISN’T SO FANTASTIC

Comparable studies have also found correlations between microplastics and other health problems. One study found microplastics may be influencing a disease called inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). It found that people suffering from IBD often have significantly more microplastics in their stool than people without IBD.

Remember the study finding microplastics in the brain? It also found a correlation between the presence of microplastics and diagnoses of dementia – but again, there is no causal link.

Minderoo Foundation is supporting research into the effects of microplastics in human health.

One review study found the chemicals in plastics such as BPA (bisphenol A) and phthalates (plasticisers) are linked to multiple health impacts in babies, children and adults.

“Plastic is toxic, whether it’s virgin or recycled, because it has toxic chemicals in it, and the plastic breaks up into micro and nanoplastics, which are like a massive army of mini-Trojan horses carrying those toxic chemicals into us,” says Dr Sarah Dunlop, Head of Plastics & Human Health at Minderoo Foundation.

While we can make small changes like filtering our water and limiting our use of plastic containers and single-use plastics, it can feel like fighting a losing battle against pervasive microplastics.

But just remember, no one has died from microplastic overdosing. That we know of. Yet.