A WA scientist has compiled the largest global dataset ever on the travel habits of large marine animals.

The collaboration involves hundreds of researchers from around the world and catalogues the migrations of some of the ocean’s most charismatic animals.

There’s more than 100 species featured, including whales, sharks, turtles, seals, penguins, dugongs and albatrosses.

Passionate about the ocean

The monumental task is the work of UWA Oceans Institute senior researcher Dr Ana Sequeira.

With a vision for a global perspective on the movement of marine megafauna, she reached out to scientists around the world and invited them to contribute.

So far, more than 300 researchers have shared their data.

Ana admits it’s a big project but says there are currently few scientific publications about the migrations of marine animals at global scale.

“I’ve always been passionate about the ocean,” she says.

“And one thing I've always been curious about is how these species travel in the global ocean.

“Specifically, how do they make choices about where to go next?”

Where are the wild things?

Ana was recently awarded a prestigious Pew Fellowship to analyse the data she’s amassed.

One of the challenges is accounting for differences in how the researchers collected data in different regions of the globe.

For instance, if 100 sharks were recorded in one location and 10 in another, it doesn’t necessarily mean there are more sharks in the first location.

The difference could be because the scientists spent more time searching for them.

So to understand the data, Ana needs to develop mathematical models to account for the biases in each dataset.

A global perspective

Ana says working on a global scale offers a different perspective on the number of animals, the amount of habitat available to them and the different regions they may move through as they migrate around the world.

Whales, for instance, can migrate from the Southern Ocean to the equator and back again every year.

“Observations of individuals in particular locations can be very relevant for local management,” Ana says.

“But they don’t provide insight about which other areas the same individuals visit while they go about their migrations.”

Animals know no borders

The research could help target conservation efforts to where they’re needed most.

Large marine animals travel through different countries’ waters and into the high seas, which make up approximately two-thirds of the world’s oceans.

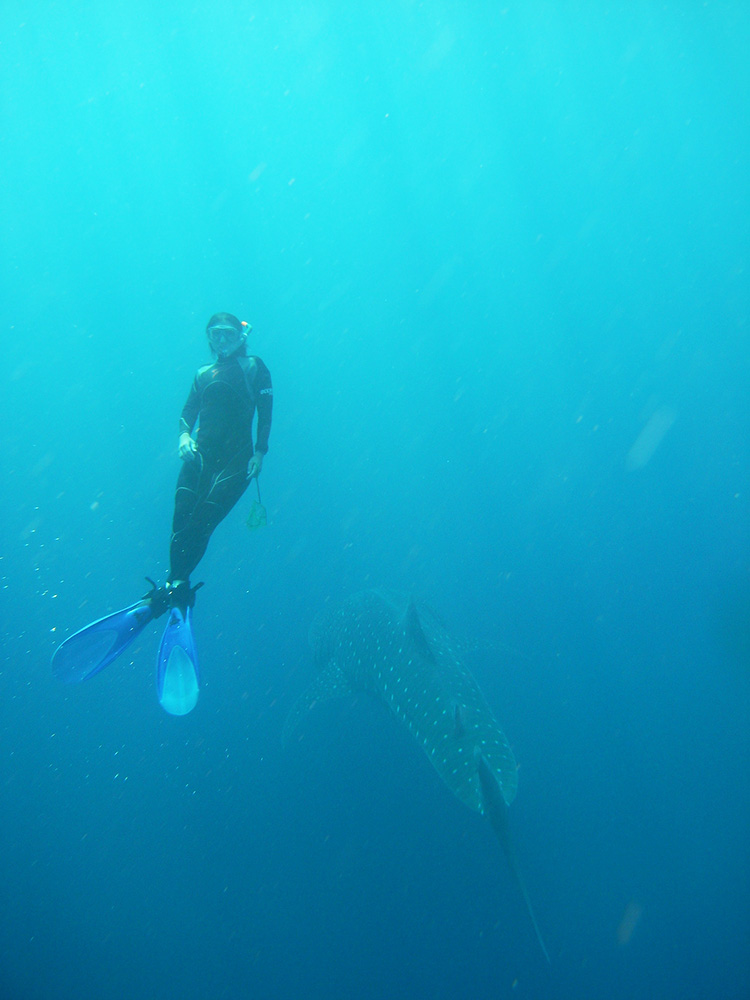

In Western Australia, for instance, whale sharks are a protected species and ecotourism activities are highly managed.

But the same individuals migrate to regions where they’re afforded far fewer protections.

“These animals don’t know jurisdictional boundaries,” Ana says.

“They don’t know where the exclusive economic zone finishes and if some waters are part of a country or another.

“To understand what they do, we need to investigate their movements at the scale they perform them.”