While Australia is one of the most biodiverse countries in the world, we also have some of the highest extinction rates.

Hopeful scientists set up thousands of camera traps across the country to build a better picture of the threats facing species and ecosystems.

But how effective are they?

SAY CHEESE!

Camera traps are devices that capture stills or videos of animals in the wild. They are triggered by sensors that detect the heat of an animal in motion.

The earliest camera trap prototypes were developed in the early 1900s to get wild animals to “take photos of themselves”. These days, they’re used in ecology and conservation, with hundreds of studies utilising camera traps published every year.

Credit: National Geographic (PDM 1.0)

Camera traps are loved by ecologists because they cause little disturbance to the behaviour and wellbeing of the animals being studied.

These devices offer other advantages. They can be active 24 hours a day and detect elusive animals.

PICTURE PERFECT?

Some of the questions ecologists can answer through camera trapping relate to species distribution, numbers and behaviours as well as changes in ecosystems – including ecological cascades.

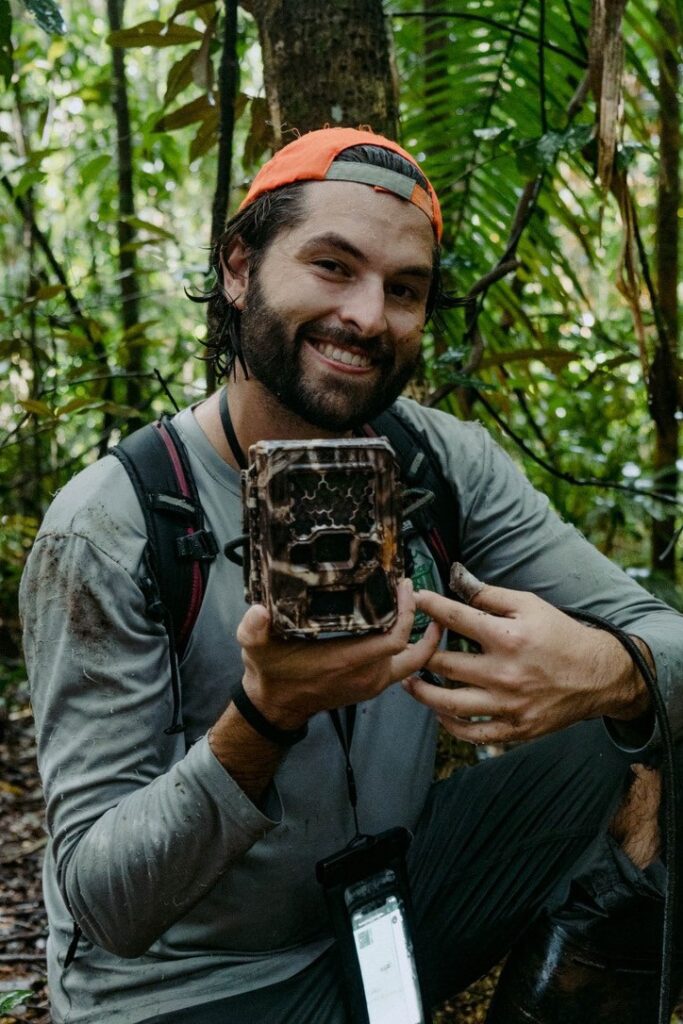

Wildlife ecologist Zachary Amir is Principal Data Scientist at the Wildlife Observatory (WildObs) in Queensland.

Credit: Supplied Zachary Amir

“When something happens in nature, it can have knock-on effects that affect different organisms,” says Zachary.

“[Ecological] cascades are multi-levelled events that ripple through an ecosystem.

“You lose your top predator, like a tiger in an Asian rainforest.

“Then the deer may become overabundant and overconsume vegetation.

“Camera traps are a useful tool for quantifying changes in predator and prey populations.”

But they only paint part of the picture.

A study published earlier this year describes some of the limitations and challenges of camera traps.

Small animals are less likely to trigger the cameras, and it can be difficult to identify similar-looking species, specific individuals or their sex from a photo or video.

One of the main challenges is processing the millions of images generated by cameras.

“People are facing major bottlenecks when it comes to turning images or videos into spreadsheets,” says Zachary.

Credit: Supplied Zachary Amir

SNAPS AND STATS

WildObs was launched in 2022 by Associate Professor Matthew Luskin and his colleagues.

Zachary, supervised by Matthew, was completing his PhD on prey-predator interactions in Southeast Asia when the idea began to take shape.

“I realised we needed a lot more data to build up sufficient sample sizes,” says Zachary. “But we had to transform and manipulate the data. We needed collaborators.”

Since then, WildObs has served as a data commons that supports image processing, data curation and analysis to turn images and videos into more user-friendly data.

“We’re still in our infancy of developing our AI models, and we are applying them to what we’re calling our wildlife image management platform,” says Zachary.

“You upload images or videos, apply the appropriate AI model to your data and download a spreadsheet.”

The current models for identifying species (like Wildlife Insights) are useful but not necessarily suited for identifying Australian animals like the musky rat-kangaroo.

“When Wildlife Insights was developing their AI model, they had never had access to musky rat-kangaroo images,” says Zachary. “It’s a good platform, but tends to be northern hemisphere-centric.”

However, Wildlife Insights has released its SpeciesNet model, which is being fine-tuned for Australian species with the help of WildObs.

Credit: Charles J. Sharp via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

COOPERATION FOR CONSERVATION

WildObs has a wide range of collaborators and partners.

“We work broadly with government, industry, universities, NGOs,” says Zachary. “Not to mention different knowledge holders and citizen scientists.”

Currently, the data processed by WildObs is shared through the Atlas of Living Australia.

However, Zachary and his colleagues hope to make the data as accessible and scalable as possible.

“Scaling up is being able to apply analysis to different datasets. We’re tracking information that enables us to share data more widely,” says Zachary.

“Then, the scalability just goes … beyond.”

And with it, conservation efforts.