That’s because you’re close to ancient hot springs that hold clues to the how life began.

But how could this discovery affect our understanding of the origin of life (and where to find it elsewhere)?

Deep Blue Sea

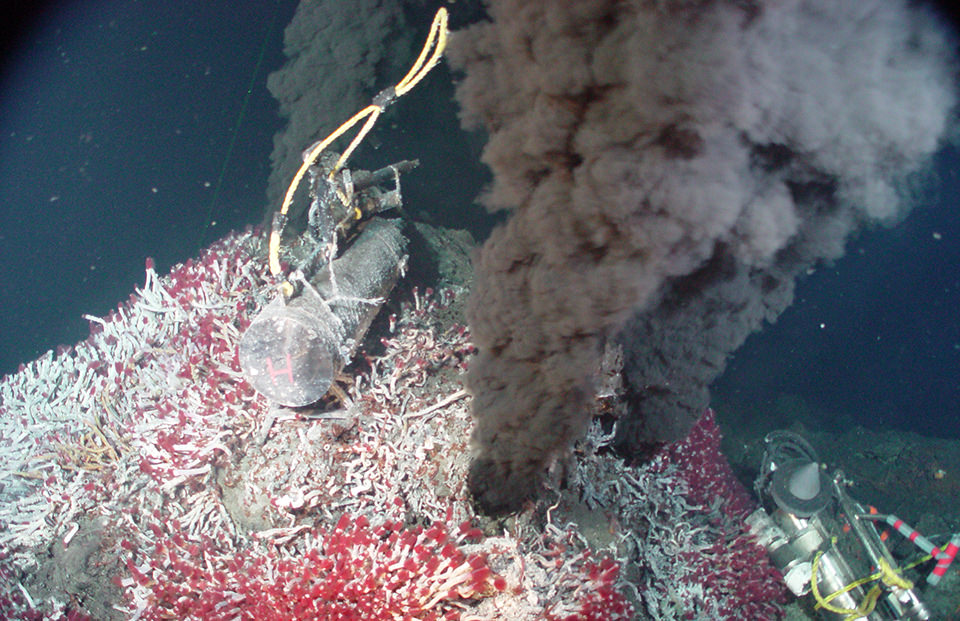

One persistent theory about the origin of life on Earth is that life began in the deep ocean with hot, acidic vents known as black smokers.

“Black smokers host an amazing biosphere and provide almost everything needed for primitive life: the right chemicals and energy from the Earth,” says Professor Martin Van Kranendonk. He is the director of the Australian Centre for Astrobiology at the University of New South Wales.

But there’s always been a bit of a snag in the theory that black smokers hosted the origin of life.

The Water Problem

Before you get even the simplest life, you need to make complex organic compounds such as proteins and carbohydrates. These compounds have to be made from simpler organic compounds like water, carbon dioxide and amino acids. And those processes just don’t work very well in permanently wet environments such as the deep sea.

This is known as the water problem.

“For life, you need complex organic molecules,” says Martin. “But the water problem shows that complex molecules require the energy from drying to bond them together and actually break down in the presence of too much water.”

And yeah, if you're wondering, the bottom of the ocean qualifies as 'too wet'.

To learn more about the origin of life, scientists needed an environment that had water and elements like carbon, hydrogen, boron, zinc and manganese, but also an environment that isn’t always wet. Enter the ancient hot springs of the Pilbara, which are 3.5 billion years old.

“Hot springs are like little Petri dishes with a huge amount of complex chemistry.”

“We have found that they provide the essential elements for the origin of life as well as the cycles of drying out and rewetting that allow complex organic compounds to form.”

It’s worth noting that similar hot springs would have been present all over the surface of the Earth. But because the rocks of the Pilbara are so old and so well preserved, they’re an ideal window into the Earth billions of years ago.

Putting the ‘astro’ in astrobiologist

The jury is still out on whether hot springs or the deep sea was the definitive environment that hosted the origin of life on Earth – as Martin points out, the black smoker theory does have a lot going for it – but the current change in thinking towards an origin of life on land that is sweeping the scientific community has impacts beyond our world.

“When looking elsewhere in the Solar System for life, NASA has always abided by the mantra of ‘follow the water’.

“This is fine if you are searching for life that was already thriving, but if you need a rocky surface to host hot springs to have a chance for the origin of life, then that changes the way we think about which planets might be suitable hosts for life.

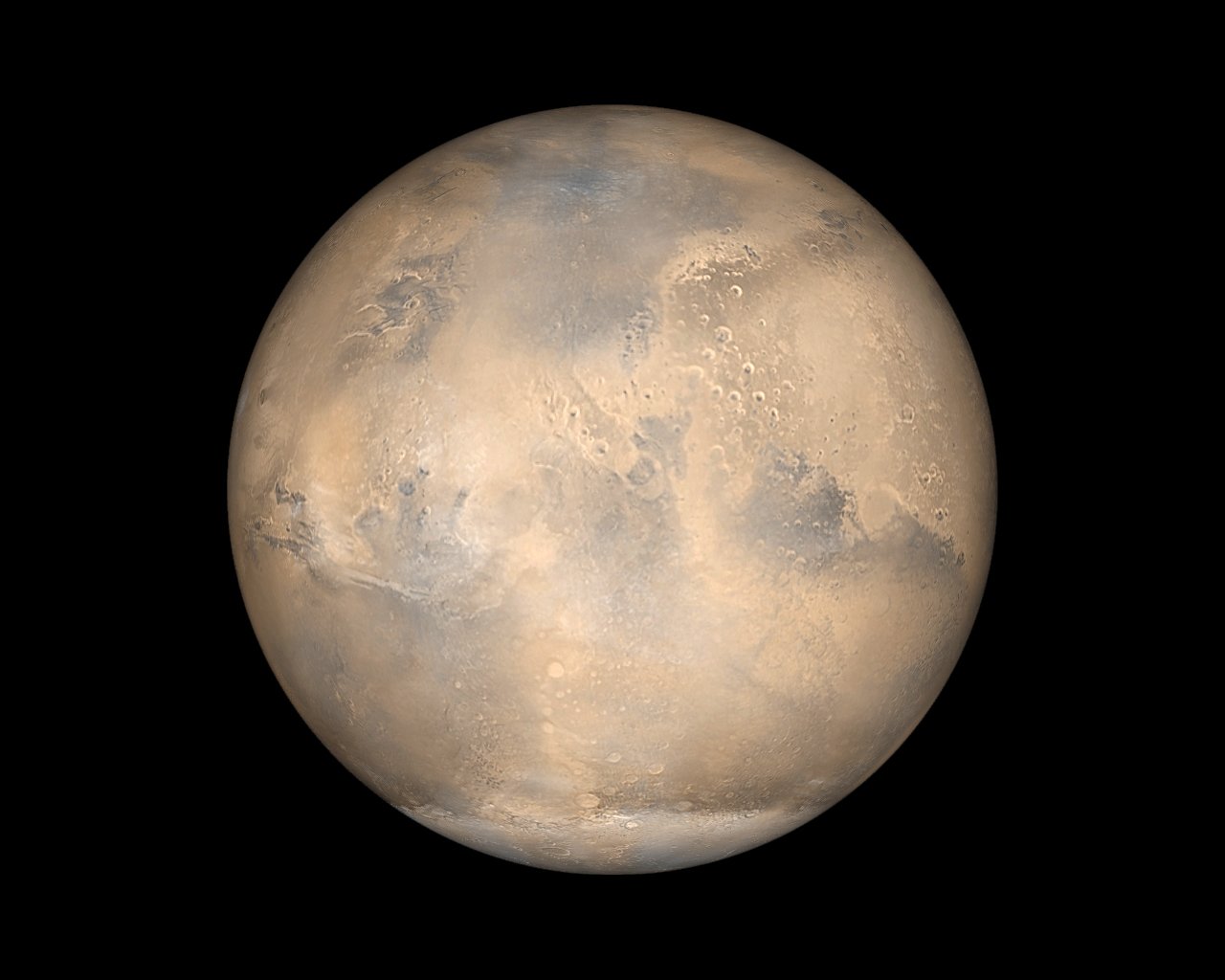

“It makes us much more interested in somewhere like Mars, which we know had volcanic heat and liquid water – the ingredients for hot springs. But more excitingly, Mars researchers have already found actual hot spring deposits.

“How cool would it be to go back and look for signs of life there?”