Plastic has a role in almost every part of our lives. The cheap, hardy and versatile structure of plastic has made it the go-to material for manufacturing.

Unfortunately, the very same qualities have also made plastic the main villain in the global war against waste.

The ARC Training Centre for Green Chemistry in Manufacturing wants to reduce the environmental impact of the manufacturing industry by finding new ways to make goods.

It works with companies and PhD students to find these greener methods.

“Green chemistry looks at how we produce the goods that we take for granted in everyday life,” says Professor Antonio Patti, Director of the ARC Industrial Transformation Training Centre – Green Chemistry in Manufacturing.

One of the aims of green chemistry is to curb the level of pollution from plastic manufacturing. It’s no small feat.

A 2017 study showed 60% of all the plastics ever produced have ended up as landfill. That is nearly 5 billion tonnes discarded.

This plastic has wound up on top of Mount Everest, frozen in Antarctic ice, in the air of our cities and in our food, beer and water.

Single-use plastic is one of the worst offenders. It makes up roughly 36% of all plastic created and is one of the largest sources of plastic pollution.

Green chemistry seeks to change this.

“Green chemistry is concerned with plastics in a big way because they’re so ubiquitous, hidden around so many applications, particularly with packaging,” says Antonio.

“We look at energy usage, renewable feedstocks, materials that that don’t leave any … ideally no pollution at all.”

The plastic trap

Plastics aren’t inherently bad. In fact, they have many unique properties. Unlike most materials, they maintain their structure at a wide range of temperatures (think about your microwave takeout containers), they resist chemical destruction and they’re cheap to make.

Even plastic packaging is useful. A 2010 paper found that, if plastic packaging was replaced with alternatives, the world would need 1,240 million GJ of power to make up the processing difference. Not only would this be more expensive for everyone, it would increase global greenhouse gas emissions by 61 million tonnes per year.

But some plastics should be replaced. Getting rid of single-use plastics like cutlery, cotton buds and straws would remove greenhouse gases.

So what can we do to solve the plastic problem without making other problems worse?

Break it down

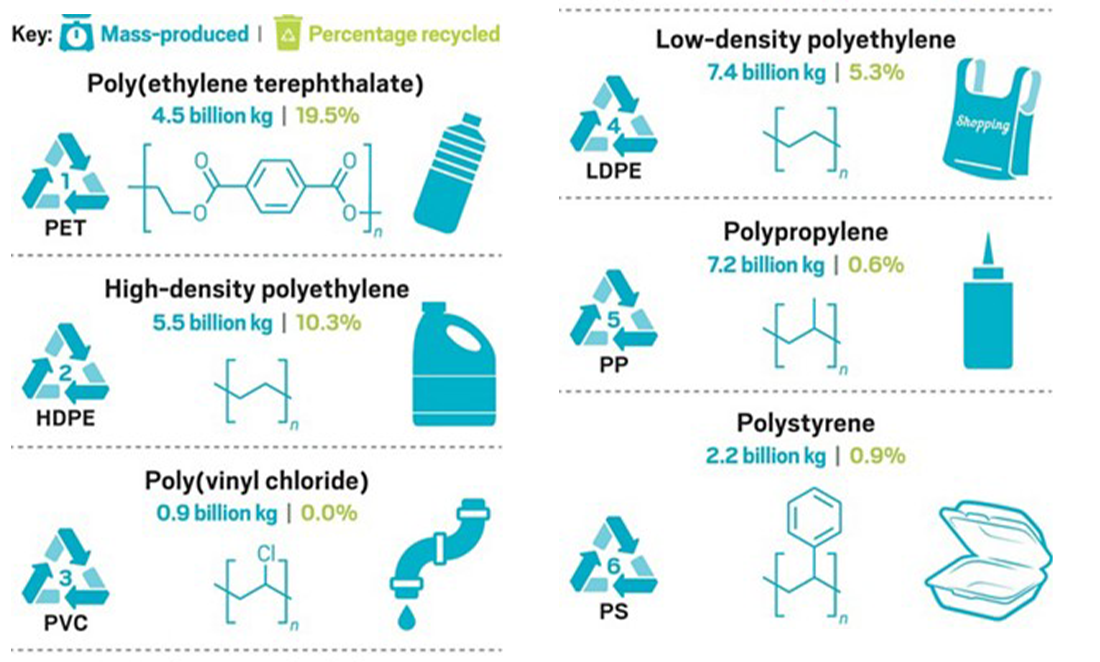

There are currently two ways to recycle plastics: mechanical and chemical recycling.

Mechanical recycling involves melting the plastic down and recasting it. The downside of this process is you can’t turn it into different types of plastic, and there’s a limit on how many times the plastic can be recycled before degradation.

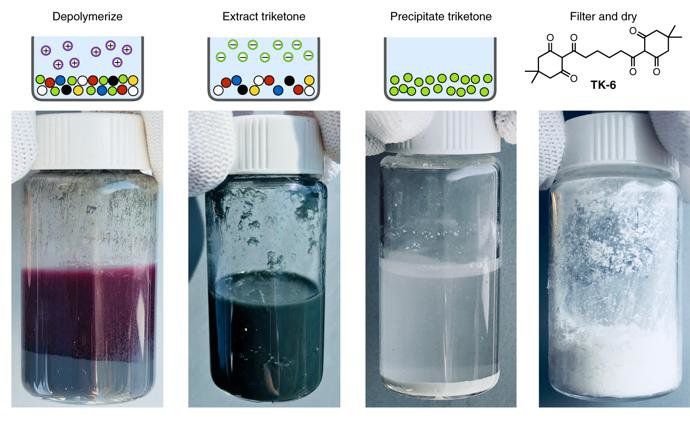

Chemical recycling breaks down plastic at a molecular level by turning the polymers into monomers (the building blocks used to make plastic).

Despite being a better long-term solution, molecular recycling isn’t being used yet because it’s more expensive and it’s experimental.

The most common way to undertake chemical recycling is through a technique called pyrolysis, which separates the plastics by melting them at different temperatures.

But it’s an expensive process where factories need to run pyrolysis chambers at up to 700°C.

Pyrolysis isn’t very good at removing pollutants from plastic either.

But for some plastics, we can skip the hot house treatments by using bacteria.

Humans vs nature

One bacterial species, Ideonella sakaiensis, was found happily munching on plastic outside a bottling plant near Kyoto.

This amazing bacteria was actually using the plastic bottles as a food source.

It did this by using an enzyme called PETase.

An enzyme is a molecule the helps chemical reactions happen in living things.

By isolating this enzyme, scientists were able to use it to break down plastic bottles by themselves.

This bacteria could help commercially recycle plastic in as little as 1 or 2 years.

But this little fella has drawbacks.

It can only break down PET plastic – the plastic from our drink bottles, which is already the easiest type to recycle.

We’d also have to be very careful about how we use it. We could accidentally introduce this bacteria into new environments. With so much plastic around the world, it’s likely to spread quickly.

Humans already have a troubled history of mucking around with bacteria. Take antibiotic resistance, for example.

People, not professors

In the end, plastic is a social problem more than a scientific one. We need to change the way we use items if we want to stop plastic pollution.

“We are moving towards more biodegradable and renewable plastic packaging, but we still have a way to go because the biodegradable methods are quite pricey relative to petrochemical-derived packaging,” says Antonio.

Currently, the manufacturers creating plastics don’t have to pay the pollution or health costs produced by plastic waste. These costs are passed on to the government and the public.

The most effective way to solve this problem is to get the government to legislate rules that ensure the plastic industry is sustainable. You could help by writing to your local MP about this.

Choosing to buy from businesses that use recycled plastics or reusable alternatives can help too. Businesses adapt to meet the demands of their consumers, so even small acts like this can make a big difference to our global fight to reduce plastic waste.