Picture the ecosystem in southwestern Australia as a Persian rug.

A beautiful expanse of colour and texture that tells a story.

As a landscape, it’s a haven for native plants and animals, many of which are only found in this part of the world.

An area so unique it’s recognised as a global biodiversity hotspot.

Throughout the 20th century, roughly 19 million hectares of land was cleared for agriculture. There was little regard for sustainability or ecological values.

This left our Persian rug in tatters.

FRAGMENTED

Before the widespread clearing, southwestern Australia was a closely woven mosaic of different vegetation types. There were banksias, she-oaks and eucalypts alongside vibrant salt lakes and granite outcrops. Now, these areas of bushland are dotted among large swathes of farmland like freckles. This is habitat fragmentation.

This process splits large, continuous habitats into much smaller, isolated areas. This is due to roads, farms or other human activities. It limits the ability of native plants and animals to survive in the long term, let alone spread.

Habitat fragmentation has been a recognised issue in WA since the 1980s. That’s when scientists became increasingly concerned about what these small pockets of habitat meant for the animals living there.

Using the Persian rug analogy, if a rug is cut into small pieces, it doesn’t create lots of smaller rugs. It leaves lots of fabric scraps fraying at the edges.

Those small scraps of fraying rugs are the national parks and reserves in South West WA.

Thankfully, a seamstress of sorts is doing its best to stitch it back together again.

LINKING

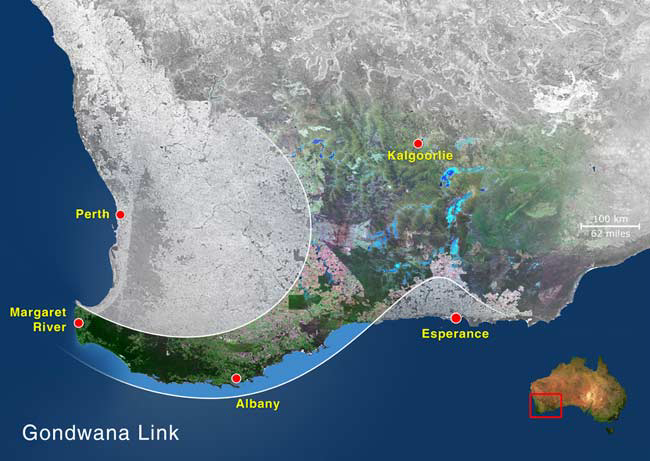

Enter the Gondwana Link program. It aims to restore a 1000 kilometre ecological pathway between Margaret River and the semi-arid inland around Kalgoorlie.

Keith Bradby OAM is the CEO of Gondwana Link and has been part of the team since its inception 22 years ago.

Keith says the land Gondwana Link manages is “one of the most connected environments in the southwest”.

Over 920 kilometres of the proposed 1000km is already habitat. Many of the groups involved with the Gondwana Link program are focused on the remaining gaps. These gaps are primarily farmland on either side of the Stirling Range National Park.

Across key parts of the Gondwana Link, some 10,000 hectares of land has been replanted with around 50 million individual plants of various species.

While this is a significant achievement, Keith says more than twice as much is needed.

Gondwana Link has chosen to focus on an area that has a good chance of being restored back to a dynamic, self-sustaining ecosystem.

“This is the perfect place to reconnect habitats. We worry that small reserves further north in the Wheatbelt are not even going to survive as museum pieces without replantings to connect them,” Keith says.

The core habitat corridor appears to be on track to be complete by the end of the decade, but “send me a big cheque and we’ll have it plugged within the next couple of years”, says Keith.

But Gondwana Link connects more than land – it connects people and culture too.

CONNECTING

When the Gondwana Link program began, its focus was purely ecological and working with landcare and environmental groups.

Now, it’s also working with Noongar groups and Indigenous rangers to help them manage their land.

“Far too many programs get wrapped up in the … science and don’t appreciate [that] the changes we need must come from people and structures changing,” says Keith.

“You can do all the studies on the yellow-bellied whatnot that you like, but it’s actually how you get people to work together. That has been our biggest challenge.”

Much of the Great Western Woodlands, part of the Gondwana Link pathway, has been confirmed as an Indigenous Protected Area (IPA) in 2020. This means that Traditional Owners have autonomy over the management of this land.

Freehold properties near Salmon Gums and Ravensthorpe have been purchased by the Esperance Tjaltjraak Native Title Aboriginal Corporation for the respective Traditional Owners.

They are restoring what Keith describes as “not very good farmland”. Funding from investors and selling carbon credits is enabling the plantings and large-scale restoration.

This site is at the top of a songline so it contributes to both an ecological and a cultural reconnection.

“It’s just wonderful,” says Keith.

RETURNING

Wilyun Pools is another area where Gondwana Link has facilitated the returning of land to Traditional Owners.

Kim Scott is a Wirlomin Noongar academic and author. He’s excited to use Wilyun Pools as a cultural base and says the data is clear.

It’s estimated that only 10% of Noongar people survived the first 50 years of colonisation, an “apartheid-like regime” until the late 20th century, and subsequent destruction of their cultural heritage.

“Wilyun Pools is an area where we’ll continue our work to regenerate cultural strength from fragmented and isolated bits of [our] heritage that remains,” says Kim. “There’s a clear parallel between cultural and ecological renewal.”

“There’s not a strong enough recognition of the trauma and damage that’s been done to the Noongar community, and having some sense of responsibility and stake in Country … through having a property is going to make it a whole lot more meaningful.”

Wilyun Pools will enable the ecological renewal of the landscape to reduce the effects of habitat fragmentation on the ecosystems while allowing cultural renewal for Noongar people.

“Our work is about encouraging cultural blossomings from a very infertile and hostile recent history,” says Kim.

WEAVING

Sewing the Persian rug back together requires a few different threads.

There needs to be an ecological thread and – perhaps more importantly – a cultural thread to reconnect people on Country.

Gondwana Link is now turning its focus to maintaining what is left of the landscape.

“By focusing here, we can give it the best chance of adapting to whatever is coming,” says Keith.

“Walking through ecosystems full of life that I once knew as bare paddocks just shows we can do it.”

The needle is threaded, but the work to stitch the cultural connection for Traditional Owners has only just begun.