PhD student Bronwyn Ayre has found that birds are much better at pollinating the Western Australian floral emblem than bees, mainly due to their size.

Working with UWA and Kings Park and Botanic Garden, Bronwyn is comparing how effective birds and bees are at pollinating the flower of the kangaroo paw.

And it seems bees just aren’t big enough.

Evolving flower shape

Over time, the plant has evolved to encourage birds to pollinate it over insects.

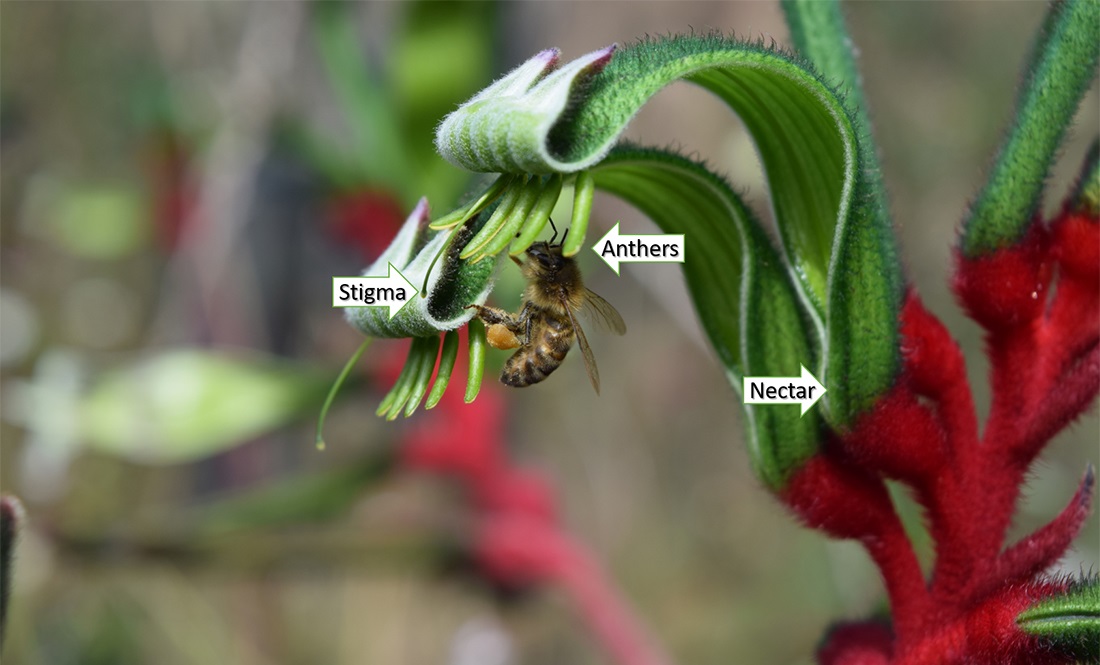

“The plant has weird-shaped tubular flowers that have a curve in them,” Bronwyn says.

“And some birds are a perfect fit in size and shape to the flower.”

Key nectar-feeding birds pollinating the kangaroo paw are the brown honeyeater, red wattlebird, western spinebill and white-cheeked honeyeater.

“This means that, when they enter the flower to take nectar, pollen covers their head and back.”

That means they gather much more pollen to transfer than a tiny bee can.

In contrast, when bees visit the flower, they’re getting the technique all wrong! They don’t actually get anywhere near the plant’s female reproductive parts and are just there to satisfy themselves.

To test this theory, Bronwyn used chicken wire to enclose the plants, excluding birds and only enabling bees to reach the plant.

She also had control plants enclosed with veggie mesh—excluding both bees and birds.

She found plants only allowing bees in produced up to 95% less seeds than those visited by birds.

Making management and conservation decisions

So why is this study important, and why have the plants evolved this way?

In the southwest of WA, approximately 15% of the 8000 flowering species are pollinated by birds and/or mammals.

This is the highest percentage in the world!

But little is known about the impact of birds and mammals on pollinating plants.

“We have highly fragmented landscapes in WA, and birds are able to travel further distances,” Bronwyn says.

“It’s quite easy to see that birds are able to share greater amounts of pollen more widely than insects can.”

This ultimately keeps up higher genetic diversity, which is useful for a species’ continued survival.

Bronwyn adds that improving our understanding of the role that birds and mammals play in pollination will allow us to make more effective management and conservation decisions.

“This is just a small part of the overall puzzle.”

“Right now, nearly 40% of plants threatened with extinction in the southwest are pollinated by birds or mammals, which is quite disproportionate.”

“Maybe it’s because birds aren’t around in these areas or they are outcompeted for resources or there are others plants being favoured over local native plants.”

Success in telling the story at Famelab

Bronwyn was selected as a WA finalist in the 2017 Australian FameLab—the world’s biggest science communication competition, produced by the British Council. Young scientists have to explain their latest research in under 3 minutes, with no jargon and no PowerPoint. They are judged on the three Cs: charisma, clarity and content. Although Bronwyn didn’t take out the top prize, she received a special mention in the final.