Dr Jennifer Lavers is a marine biologist with the Esperance Tjaltjraak Native Title Aboriginal Corporation.

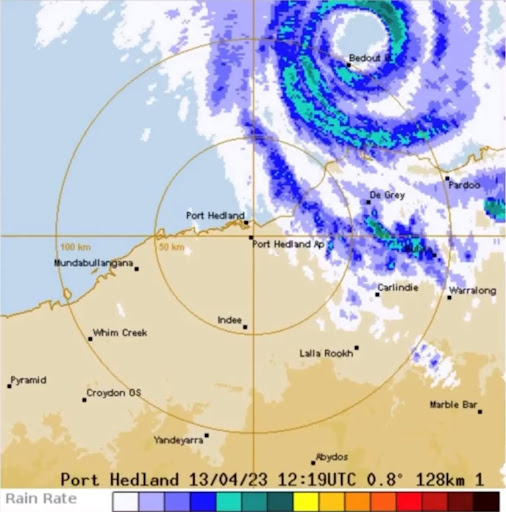

Jenn has been working on Bedout Island since 2016. Only 48 hectares in size, the island sits 96 kilometres northeast of Marapikurrinya (Port Hedland).

Despite its size, Bedout Island is one of Australia’s crown jewel hotspots for seabirds. When Cyclone Ilsa hit the island in 2023, Jenn was gravely concerned for the birds’ survival.

Jenn and her team have just released a study, over a year after the storm, revealing the devastating extent of the impact.

THE CALM BEFORE THE STORM

“Front to back, top to bottom, it [was] completely covered in a large number of different seabird species,” Jenn says. “It’s a real Mecca for biodiversity.”

The island can host upwards of 25,000 individual seabirds of at least 10 different species. The birds support a variety of ecosystems surrounding Bedout Island, as these animals can move nutrients between land and water.

The jirli waanyja/masked booby (Sula dactylatra bedouti) is a striking inhabitant of Bedout Island.

It has a wingspan of 160–170cm and can weigh up to 2kg. It’s mostly white with black-trimmed wings, and as its name suggests, it looks like it’s about to attend a masquerade ball.

Bedout Island hosts the only population in the world of one jirli waanyja subspecies, making them vulnerable to extreme climate events like Cyclone Isla.

A MASS GRAVE OF SEABIRDS

Four days after the cyclone, Jenn convinced a media helicopter to do a flyover of Bedout Island.

“I cried when I saw the photos,” Jenn says. “I just sat and stared at my computer.”

Images from the flyover show sandy shores covered in little black dots. From a closer vantage, it becomes clear that each dot is a dead seabird.

The island now hosts a mass grave of seabirds with no vegetation left at all.

Jenn says that she is “gravely concerned” about the masked booby, because there are now only 40 individuals left.

The kuyangarti/lesser frigatebird (Fregata ariel) and purralyakura/brown booby (Sula leucogaster) were also heavily impacted by the cyclone.

A LOT OF UNKNOWNS

Based on a combination of aerial and ground surveys conducted after the cyclone, it’s estimated that only 10–20% of these birds have survived. That means that tens of thousands of seabirds were killed in the cyclone.

However, Jenn still does not know if these birds could become extinct any time soon.

“A lot of the critical data we would need to make predictions is missing,” she says.

The island is extremely remote and access can be restricted, making it difficult to get this data.

Jenn says that there are “zero estimates of survival rates” for any of the seabird species on the island.

More concerningly, the number of cyclones expected to hit Bedout Island is increasing. As climate change worsens, so does the frequency and intensity of cyclones.

“THE NEW NORMAL”

The storm was one of the biggest to ever hit the Australian coastline. This species wipeout is unprecedented but will unlikely be the last.

Using estimates from other ecosystems that have been hit by cyclones, Jenn predicts that seabird populations on Bedout Island could recover in 10–15 years.

The only problem? Cyclones are expected to arrive every 7 years.

“It’s pushing the limits of species to recover,” Jenn says.

In the last 12 months alone, Bedout Island had three extremely close calls with other cyclones.

“Cyclone Ilsa is not unique or rare or uncommon,” Jenn says. “This is actually the new normal and the reality is that the birds will not have time to recover before the next one hits.”

THE REBUILD OF BEDOUT ISLAND

Work to return the seabird populations to their former glory is now under way.

Without these animals, Bedout Island and surrounding ecosystems could cease to exist.

Even though the data doesn’t look promising, Jenn still has hope.

“There’s some reasonable numbers left that gives me confidence that, if we don’t have a cyclone for a while, they could actually recover and do quite well,” she says.