For West Australians, casting a line is a popular pastime.

But recent research has found prized species like the iconic WA dhufish and snapper have declined over time.

To replenish these depleting populations, the WA Government has introduced reforms to demersal fishing.

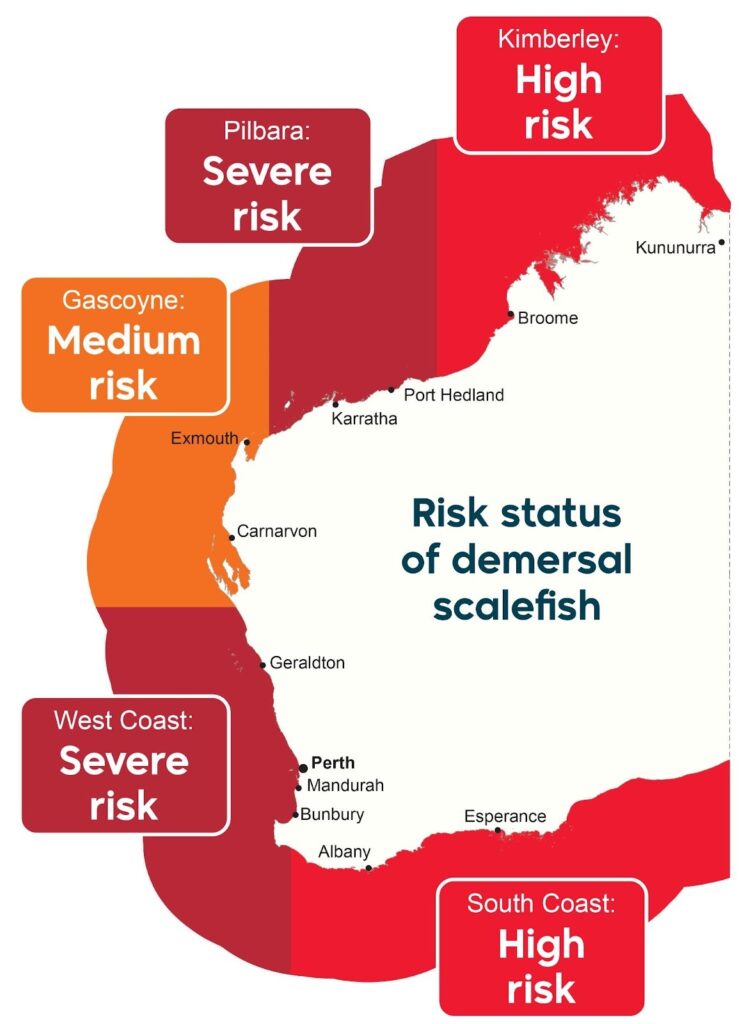

This includes a permanent ban on commercial fishing in the West Coast bioregion, which stretches from Kalbarri to Augusta, and a pause on recreational fishing of the species until spring 2027.

Other popular fishing zones have also had restrictions tightened, with 50% catch reductions introduced across the Kimberley, Pilbara and South Coast regions.

“This is not a popular decision,” says Matt Roberts, Executive Director of Conservation Council of Western Australia.

“It’s a government who’s had to make a decision because the science has demonstrated what has been evident and what people have been warning about for years.

“The advice that they were getting was that the fishing stocks were just critically low and that we had to take some action to try and recover them.”

BELOW THE SURFACE

Demersal fish are typically found living near the seafloor and include a range of species, including pink snapper and dhufish.

In the West Coast bioregion, both of these species have declining populations.

Scientists have tracked their populations by assessing spawning biomass, which is the total combined weight of all mature fish in a population capable of reproducing.

Credit: Supplied by Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (DPIRD)

For dhufish in the West Coast bioregion, spawning biomass is 85% depleted. Northern and southern snapper are 83% and 80% depleted respectively.

“Many of … our demersal species on the West Coast are slow growing and they live in a low-productivity system,” says Associate Professor Tim Langlois from UWA’s School of Biological Sciences.

“Every 10 years or so, we get a bit of a pulse of replenishment or recruitment.

“[This] makes it really hard for fishery scientists to manage the fish stock to ensure there’s enough big breeding fish around to replenish the population.”

Size matters when it comes to reproduction, research shows. Larger fish produce significantly more eggs, making them critical to recovery.

For example, a 40 centimetre pink snapper can release 100,000 eggs, while a 70 centimetre pink snapper can release more than 500,000.

“The science has been building for a long time, suggesting that we need a management reset and consider how we can better manage these species in the fishery,” says Tim.

“We’ve got a great example of government listening to science and acting on science.

“Now it’s the chance for the science and the community to come together and come up with a way where we can try and ensure that we can buy fish and catch fish on the West Coast [in] the future.”

But the decision to pause demersal fishing has also impacted the livelihoods of some West Australians.

Credit: Supplied by Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (DPIRD)

THE HUMAN COST OF REFORM

The permanent closure will largely impact the commercial fishing industry, which contributes more than $1 billion to the state economy each year and supports around 10,000 local jobs.

To help the industry during the transition, the WA Government has committed $29.2 million over 2 years to support affected fishers and associated businesses.

Approximately $20 million of this funding has been allocated to a compulsory buyback of commercial fishing licences.

“It is crucial that it is done thoughtfully and that people are compensated and assisted to turn to whatever else they can do to ensure that they get an income,” says Matt.

“It’s something that we all need as a whole of society and they shouldn’t have to bear the brunt of that.”

For recreational fishers, opportunities to throw a line into the water remain.

Demersal species can still be caught from beaches or jetties, while boat fishing for other species like whiting, yellowtail kingfish and mahi-mahi is still permitted.

While the closures will remain in place for at least the next 2 years, it’s hoped the pause will give fish stocks the best chance of recovery.

“There is still hope and there are still actions that we can take, but what we can’t do, and what this ban has demonstrated, is we can’t keep kicking this can down the road,” says Matt.