Fairy wrens are everywhere. Go anywhere in Australia and there will be at least one local fairy wren.

They’re not endangered. In fact, it would be hard to imagine an animal less endangered than fairy wrens.

So what do we gain from researching them? Quite a lot actually.

Beyond Bird Watching

Dr Lyanne Brouwer has led a team researching red-winged fairy wrens near Manjimup since 2008.

“It’s not an endangered species, but still it can lead us to very useful insights in how birds, for example, adapt to changing climates,” says Lyanne.

On the surface, fairy wren research sounds like a fun bit of bird watching, but Lyanne says it involves a lot of skills.

Credit: Asch Nighthawk, 2026

“It’s really, really hard to monitor these birds. You need to be able to use binoculars and really quickly identify individual birds.

“It’s quite hard to actually find them and watch them for a little while to work out what they’re doing.”

Identifying individual birds would be nearly impossible without some help. To make it easier, the team puts unique coloured bands around the legs of all the red-winged fairy wrens in the area.

For adult birds, that means setting up nets that are constantly monitored. The moment a fairy wren gets caught, a researcher is there to process it.

For baby birds, the team tries to locate the nests and band the birds while they’re still fledglings.

“They’re not really aware of what’s going on, so it’s much less stress for these birds,” says Lyanne.

Credit: Asch Nighthawk, 2026

Baffling Behaviours

While the fledglings might not know what’s going on, the adults certainly do. What they do with this awareness is fascinating.

“There are 10 species in Australia, and in all these species, the male offspring delay their dispersal and stay with their parents,” says Lyanne.

“The females usually disperse. So once they reach independence at about 3 months old, they start moving around.”

Among Manjimup’s red-winged fairy wrens, the male offspring stay with their parents to help raise their younger siblings – just as expected.

However, in this particular population, so do the females.

Sex-biased dispersal is conventionally understood to help a species avoid inbreeding. Curiously, the fairy wrens appear to have developed different means to achieve that end.

“One of the behaviours they show is extra pair mating,” says Lyanne. About 70% of female fairy wrens in the population will mate with a second bird outside their pair.

“It’s promiscuous mating. The females typically mate with another male. They go to another territory, they mate with the male there and they lay their eggs in their own territory.

“This is a mechanism, probably, that helps with inbreeding avoidance.”

Credit: Asch Nighthawk, 2026

The Climate Conundrum

It’s possible that the red-winged fairy wrens’ behaviour could be a climate adaptation.

Lyanne says adverse weather can make everything a lot harder for these birds.

“If they have these extra helpers, that can reduce the pressure to take care of this brood.”

Just how much climate change is affecting animal behaviour is still an open question in Manjimup and around the world.

“These sort of questions need long-term data,” says Lyanne.

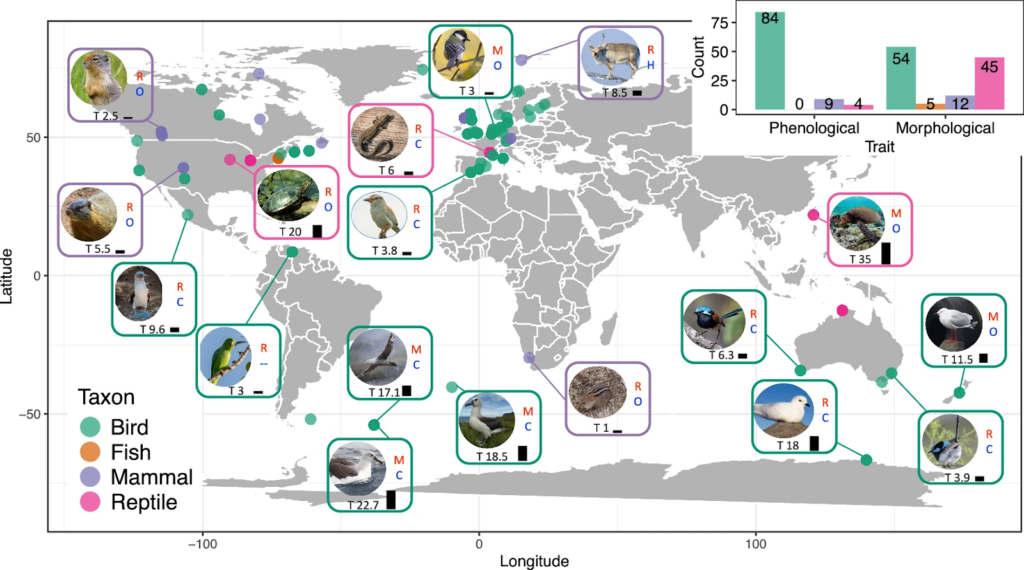

With data since 2008, Lyanne and her team contributed to a recent paper that analysed 213 species around the world to better understand how changing climates are changing the world around us.

Credit: Radchuk, Jones, McLean et al., 2026. (CC BY 4.0)

Of course, this isn’t the end of the story. As is the way with science, for every answer, there are always a thousand more questions.