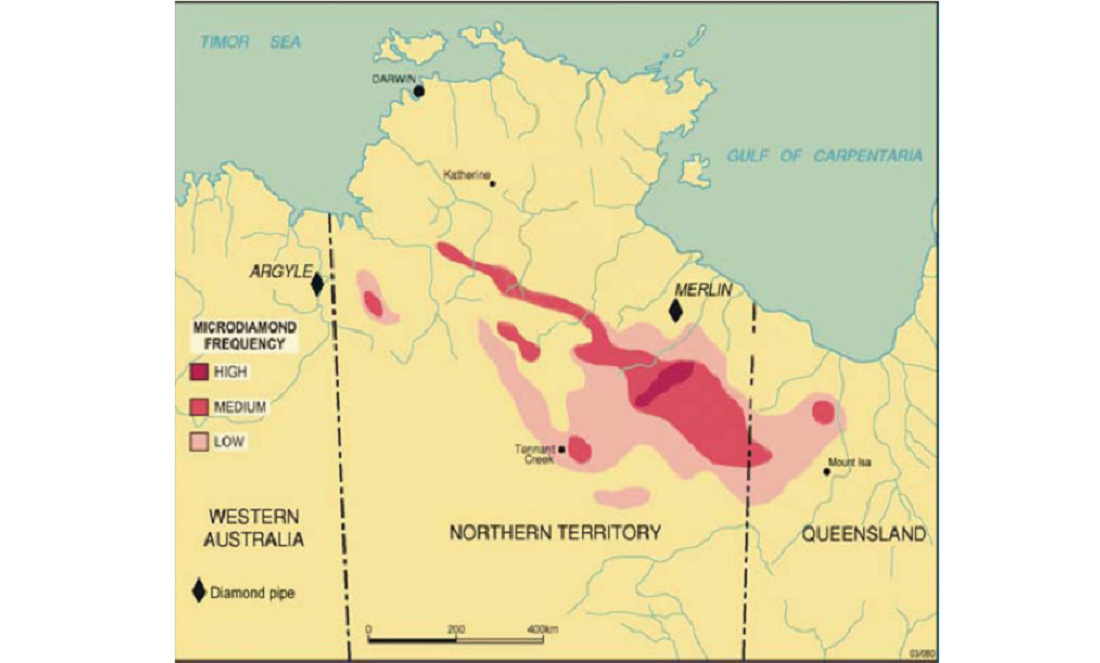

“There’s a layer of loose diamonds scattered across the Northern Territory,” says Curtin’s Professor Brent McInnes. “But we haven’t found their origin.”

The diamonds probably came from an underground pipe of diamond-rich rock, called kimberlite.

But which pipe?

Tracking diamonds is notoriously difficult; however, zircon crystals found in diamond deposits are now providing good leads.

Treasure map: helium-style

Brent and his team are the inventors of RESOchron: a rapid analysis system for measuring helium abundances in rock.

The device determines the relative concentrations of helium, thorium, uranium and lead in rocks and crystals—including zircon.

“We can use the relative abundances of these elements to work out the time-temperature history of a rock.” Brent explains.

This record acts like a chemical signature, characterising different rocks from various ages.

Low-helium hints

When Brent’s team used RESOchron to analyse zircon from diamond deposits, they discovered the crystals are uniquely low in helium.

They also determined each crystal’s uranium-to-helium content, to determine its age.

“We can then fingerprint where the kimberlite pipe is because we have a good understanding of the age of kimberlite pipes in Australia.” Brent says.

RESOchron can analyse up to 500 samples a day, which streamlines the treasure-hunting process.

It’s also useful for understanding volcanic eruptions, monitoring earthquakes and understanding how mountains were created millions of years ago.

So where are those pesky diamonds? We’ll let you know…

What’s up with helium supplies?

Helium is useful for much more than finding diamonds.

It’s vital to everything from deep-sea diving and spaceflight through to semiconductors and MRI machines.

Yet it’s destined for depletion.

The US has been sitting on a huge helium stockpile since the Cold War, but times are changing.

“That stockpile has been commercialised and is going to be depleted within the next decade.” says Brent.

“At that time, helium will become a commodity, like oil, or gold, or copper or zinc.”

Where does helium come from?

Almost all the world’s helium is generated underground through the radioactive decay of uranium and thorium atoms.

“Uranium and thorium are present in nearly every mineral in trace amounts.” says Brent.

These elements radioactively decay over time, producing particles that form helium atoms.

In time, the helium escapes from the rock, “just like it escapes through the pores of a balloon.” Brent explains.

Once on the surface, the lighter-than-air molecules race into the vacuum of space, never to fill a balloon again.

Australia is under-explored for helium, says Brent, so it’s possible we could be home to valuable helium deposits…as well as diamonds.