If you cast your mind back to high school biology, you might remember photosynthesis. It’s how plants turn carbon dioxide, water and sunlight into sugar and energy. However, not all of us are familiar with the process of plant respiration.

In a recently published research paper, a team of scientists from the UWA School of Molecular Sciences have revealed a previously unknown process that determines how much carbon dioxide plants release into the atmosphere.

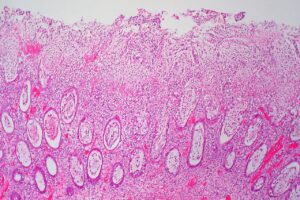

“Plant respiration, in principle, is quite similar to how our own mitochondria use a substrate that has a high energy content to create energy that the cell can use,” says Xuyen Le, PhD candidate at UWA.

“The difference is, they need the sugar that they make from photosynthesis in the day so they can burn it at night.”

Burning those sugars for energy produces carbon dioxide. Any excess sugar that hasn’t been used for energy is stored within the plant as biomass.

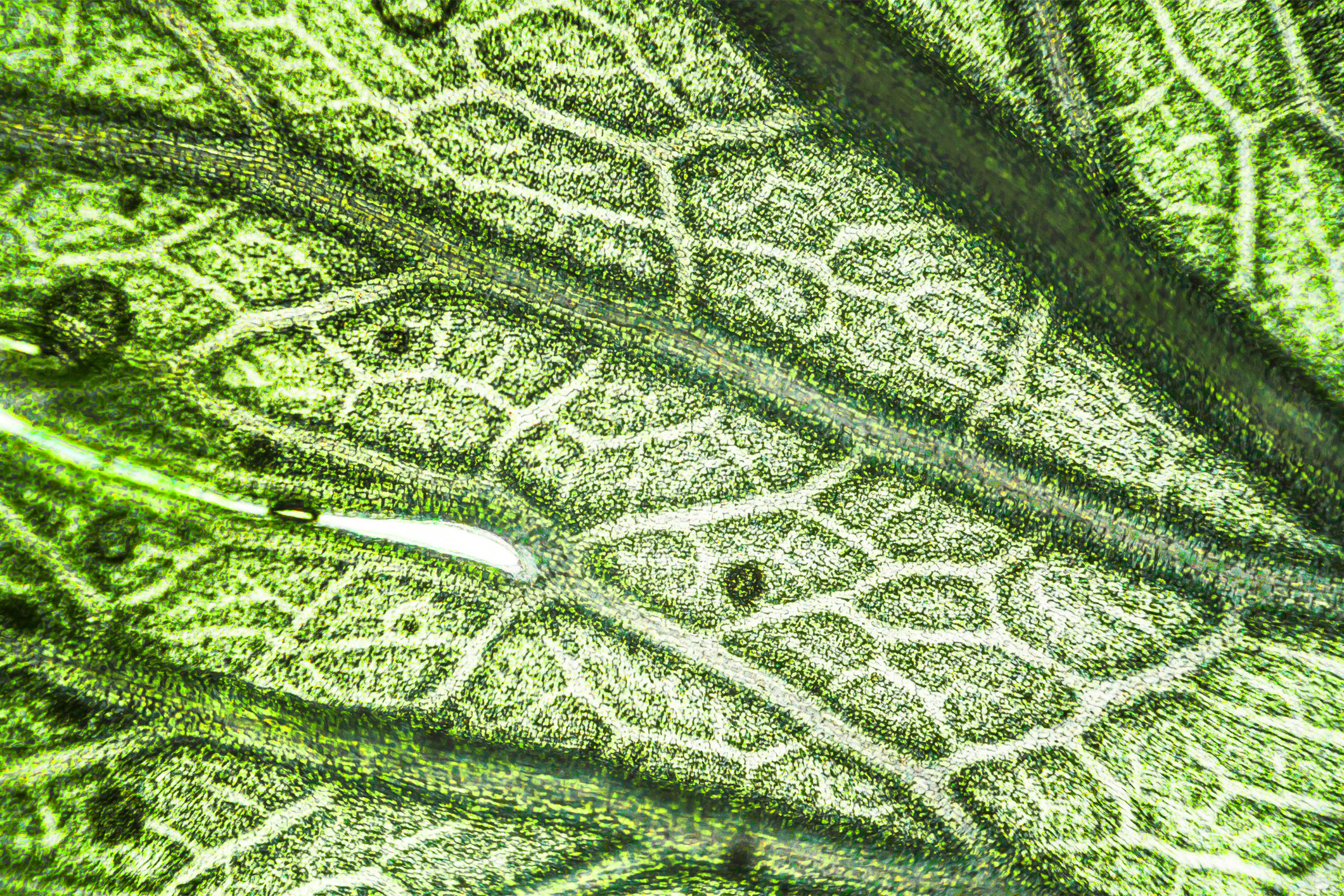

The chemical process of respiration is complex. As a result, the team of researchers focused their study on one important molecule – pyruvate.

From little things, big things grow

The name ‘pyruvate’ comes from the Greek word for fire. The molecule is so called because it is burned (technically, oxidised) to produce energy for plants.

The molecule is produced from fats, proteins and carbohydrates. Each source releases carbon dioxide when used to power respiration. However, pyruvate produced from carbohydrates releases 20–30% more carbon dioxide than pyruvate made from fats or proteins.

And as it turns out, plants can choose which pyruvate source they use.

“Somehow, they can choose which one to use and prefer the [carbohydrate source] pyruvate for respiration,” says Xuyen.

Unfortunately, this means that plants are choosing to release more carbon dioxide.

“What we really want is plants that make the amount of energy they need … but to do it for the least amount of carbon released,” says Professor Harvey Millar, a world leader in plant science who also worked on the UWA research.

The pathway of least carbon

The way plants produce energy is inefficient, and they often produce more energy than they need.

“Some of them really use a lot of energy, and it’s kind of unclear why it would be necessary to do it that way,” says Harvey.

And so the team have proposed a new process to slow down the respiratory process in plants and reduce their release of carbon dioxide.

“We found out that there are three pathways to provide pyruvate for the mitochondria to do respiration,” says Xuyen.

“When one was blocked, the other two are active and they increase their capacity so that they can meet the cell’s needs.”

By blocking pyruvate pathways, they hope to prioritise energy sources within plants that limit the release of carbon dioxide.

By limiting unnecessary energy production, they aim to redirect the carbon into biomass instead of carbon dioxide. This could be a big deal for how we use plants as food sources and carbon stores in the future.

“You can really change the plant's potential to keep carbon, have a good yield and also help the environment at the same time,” says Xuyen.

Is the future plant-based?

While it’s still early days, the potential applications of this discovery could be significant.

Crops could grow larger and be more calorie rich. Revegetation projects could be accelerated. Timber could be grown faster and plants could store carbon dioxide at a much faster rate.

“We use agriculture to make food and that’s really valuable, but it’s also … how we protect the health of our atmosphere,” says Harvey.

The team hope this new understanding of plant biology can be part of a collaborative global effort to combat climate change and aid food security.